It has become a truism that divided parties do not win elections – but Labour almost won the last election while divided from top to bottom. And who can claim that Labour was united in 2005? Despite the divisions of the Iraq war, top-up fees and the Blair/Brown power struggle, Labour purred to a majority of 66. In contrast, Ed Miliband prioritised unity in the run-up to the 2010 election but was defeated. Some now regret not speaking up while Miliband’s leadership of the Labour Party was going awry.

The Machiavellian among us might wonder if division could in certain circumstances improve electoral fortunes. As Jonathan Freedland has pointed out, in 2017 Labour managed to win the votes of both those voting Labour because of Corbyn and those voting Labour despite him. Labour’s approach to Brexit also allowed it to deliver very different messages in different seats.

So, perhaps unity is not vital to electoral success. Nevertheless, Labour should be concerned about unity. Firstly, Labour’s historic mission is to be a big tent; it was, after all, founded by both the trade unions and middle-class Fabians. In the long run, it is only by being a big tent that we can defeat the Tories and put progressive policies into practice. Up to a point, the diversity of Labour creates a healthy tension – but, taken too far, lack of unity can threaten Labour’s very existence. Secondly, governing when disunited is messy and difficult. Ask John Major, or, for that matter, Theresa May. If Labour wins the next election, it will have enough challenges without having to deal with being divided. Thirdly, unity is eminently achievable for Labour. During the general election campaign there was a semblance of unity and that should now be deepened and made permanent. Nothing breeds success like success and nothing breeds unity in political parties like electoral success. Yes, there are certain areas like elements of foreign policy and Trident where there are deep divisions between Jeremy Corbyn and many Labour MPs and members. However, in the vast majority of areas there is common cause – just as was the case when Corbyn was a backbencher and Tony Blair was Labour leader. And I am not suggesting that total unity is needed. Differences are healthy so long as they do not become too accentuated.

So how do we achieve unity in the Labour party? Most important of all to achieving unity is a commitment from all parts of the Labour party to work together in a spirit of good faith and mutual respect. I believe that, other than for a small minority, this commitment exists. This was apparent during the general election campaign, when everyone in Labour pulled together to take on the Tories. Witness Momentum’s brilliant “My Nearest Marginal” website, which funnelled canvassers to marginal seats regardless of the political leaning of the Labour candidate. On the right of the party, many MPs with misgivings about Corbyn avoided the airwaves to limit stories of Labour infighting. Since the election, Corbyn has reached out to his critics, returning Owen Smith MP, his one-time leadership challenger, to the shadow cabinet. While it cannot be expected for Corbyn to sack those who have been loyal in favour of those who were not, some further symbolic moves to bring one-time critics into the fold would be welcome. For example, bringing Progress chair Alison McGovern back into the shadow team would be a signal of intent to draw from the diversity of talents in the party.

Now with conference on the horizon, the relative harmony of Labour could be shattered. Broadly, there are two types of division between the right and left of the party – those to do with policy and those that concern the Labour Party’s democratic structures and organisation. In relation to policy, as noted earlier, the differences are largely reconcilable and it seems unlikely that there’ll be a big bust-up at conference over policy.

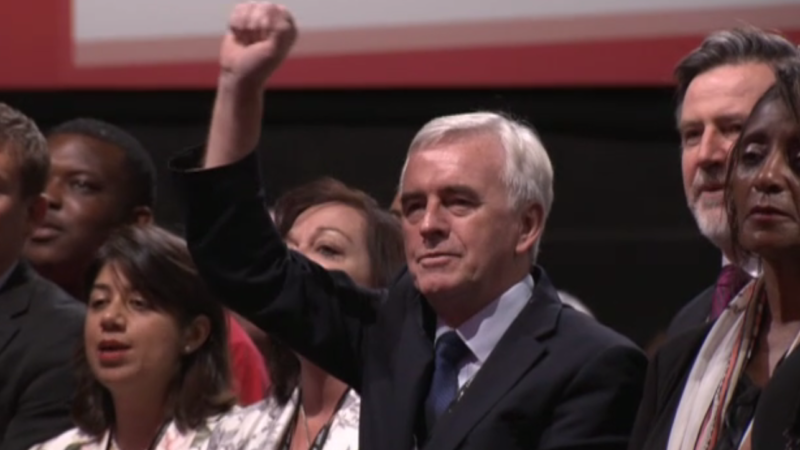

On the party’s structures, the left and right are each taking positions that are conveniently aligned with their electoral interests. On the one hand, Momentum is keen for conference to pass the so-called “McDonnell amendment”, which would lower the threshold of nominations needed to get on the ballot paper in a leadership election from 15% to 5% of Labour MPs and MEPs. It has been named the “McDonnell amendment” as it would supposedly benefit John McDonnell as Jeremy Corbyn’s heir apparent. The right of the party, meanwhile, is concerned about the threat of mandatory reselections and deselections.

How about this for an idea: rather than allow conference to divide us, the left and right of the party do a deal for peace. The right could let the McDonnell amendment pass at conference and the left could make crystal clear once and for all that it will not pursue deselections or the introduction of mandatory reselection. Then, rather than fighting with one another over conference, we can instead turn our focus to taking on the Tories.

Omar Salem is a Labour Party member in Hackney South and Shoreditch.

More from LabourList

Ashley Dalton resigns as health minister for cancer treatment

Paul Nowak column: ‘Labour must focus on the basics’

‘Labour’s two-child cap victory rings hollow while asylum-seeking children remain in poverty’