Most of the recent commentary has, for obvious reasons, focused on Theresa May and the Tory soap opera. It doesn’t seem partisan to say that the government seems preoccupied with day-to-survival and the prospects of individual would-be leaders rather than any coherent long-term agenda. Regardless of the unfortunate incidents at their Manchester conference, a Conservative conference speech whose central features were borrowed from Ed Miliband’s 2015 platform does not suggest a party with vision.

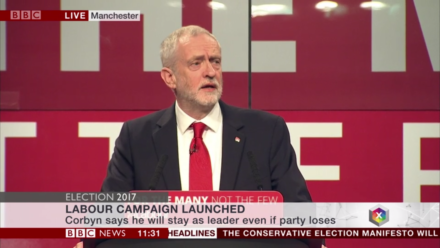

Where does that leave Labour? Only modestly ahead – typically by two to four points in recent polls. To summarise the positives: perhaps a quarter of the electorate are really enthused; Corbyn is now quite respected – in many cases even loved – and not a major vote-loser; vocal internal dissent has diminished to negligible levels; and the momentum of recent years suggests that the next election is Labour’s to lose. Governments tend to shed votes over time and when they reach the stage of forgetting what they are for then they are usually on the way out.

So why isn’t Labour further ahead? Partly because it’s only four months since the election: most people feel they’ve only just voted, and see little reason to think further. Governments usually have miserable mid-terms, but we are nowhere near mid-term.

For the opposition to lead at all immediately after losing an election is unusual. However, it’s also clear that the traditional weaknesses of Labour remain: most people think the party best on concern for ordinary people and public services but nurse doubts about whether they are economically sound. Not that most people believe the “Labour will copy Venezuela” stuff (most people would struggle to find the Latin American nation on the map, let alone assess their economic policies), but they are not sure that the economic outlook is secure. The Labour conference missed a trick on this: instead of majoring on PFI, something that most people only vaguely understand, the opportunity should have been taken to ram home a firm “fair but realistic” agenda.

Labour is right to stay free of definite policy positions on Brexit: the party can’t change the outcome of the negotiations, and needs to be free to take a view when they conclude. Nor does it need to appoint an array of past dignitaries to prove its attachment to common sense: I like Yvette Cooper, for instance, but I doubt if many voters much care whether she’s chair of a select committee or a shadow minister. But it needs some counter-intuitive statements to show it’s ready for government.

They key person here is John McDonnell. Intelligent, affable and reasonable-sounding, he has a willingness to make ruthless compromises with his beliefs that Jeremy Corbyn does not.

It doesn’t matter much that Corbyn is widely seen as more genial (McDonnell says himself, “Jeremy is teaching me to be a nicer person but I’m only halfway through the course”): few chancellors or shadow chancellors are loved. But he is hard-headed and should show it, for example by announcing a deep analysis of the priorities for the next Labour government, front-loaded with encouragement to invest. It would also be an opportunity to identify some policies as only to be done gradually as finances allow – one possibility being to absorb the railways as contracts expire rather than carrying out instant nationalisation. Corbyn and McDonnell have plenty of leeway before anyone accuses them of selling out.

I am a Labour member of 46 years’ standing and a strong supporter of Jeremy Corbyn in both leadership elections: I think his combination of solidarity for ordinary people under threat in our fast-changing world, along with essential decency and civility, makes him exactly right to lead Britain.

I also think that Britain is ready for a serious socialist government: people are absolutely fed up with a capitalist society that offers them no realistic personal prospects. But I am trying to be objective here. We don’t need at this point to show we are reasonably competent and united: compared with the Conservatives, that battle is won. We need to show that we are also an economically safe option rather than reckless, recognising that not every change can be achieved on day one. If that can be achieved, then we will be extremely hard to beat, whenever the election comes.

Nick Palmer was MP for Broxtowe between 1997 and 2010.

More from LabourList

‘The case for rearmament is becoming increasingly difficult to ignore’

‘Labour must prove it understands public anger over water company failure – and act on it’

‘Education, education, education – not debt, debt, debt’