Throughout the last few years, Labour politicians have spearheaded the fight against loneliness. Before her death, Jo Cox set up a commission to tackle the subject as it was something she held close to her hear, even dedicating her maiden speech to the values of community, shared experience and the fact that we have more in common, and since then, the commission, co-chaired by Rachel Reeves, has taken up Jo’s legacy.

The commission organised a national “great get together” to encourage communities get to know each other, it was held last year on the anniversary of her death, and this year it will be held on June 22, Jo’s birthday. Last year thousands of people got together at community centres, local parks and town centres to celebrate their community- I was one of 9.3 million who attended events.

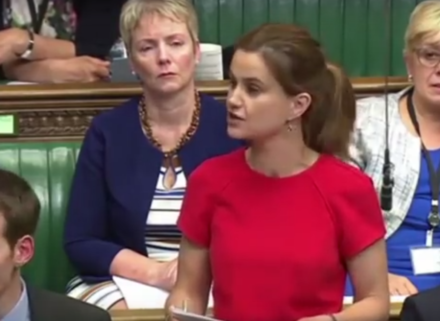

Reeves has gone on to deliver groundbreaking work on the subject. She, along with Seema Kennedy, published a pamphlet outlining how loneliness costs the economy £32bn per year and can be as harmful as smoking 15 cigarettes a day. Reeves also secured a debate in parliament, allowing MPs to discuss the matter and find a solution.

With the government’s appointment of Tracey Crouch as the new minister for loneliness, the Conservatives took an important step to tackling this problem. Up to nine million people are reported to be always or often lonely, and a 2014 study found Britain to be the “loneliness capital of Europe”.

For many, loneliness is a hidden problem; those who it attacks, chiefly, the elderly and the isolated, are often incapable of asking for help about it. It suffocates and represses to the point where it feels as though you are surrounded by truly no one, despite being surrounded by almost everyone.

Gone are the times when we could defend against it by talking to our neighbours, talking on trains or engaging with the local community- even from someone as young as me, the classic “good morning” nod of the head is now often met with bizarre squints or muffled protests as if it was a small dog that just barked at them, not a lanky young man.

This is a problem not unique to Britain, but amplified here. In other countries, however, loneliness has been beaten back. Many in the Arab world have extended families with cousins, grandparents, aunties and uncles all within relative proximity, and to this end the United Arab Emirates appointed a minister for happiness in 2016. They are leaps and bounds ahead of us in this area.

Labour should show their commitment to the struggle and replicate this new position with a shadow minister for loneliness. This minister should continue to build upon the existing work of Labour MPs but also go one step further by pledging to introduce schemes to allow primary school children to visit elderly care homes.

From working in a care home for two years, I learnt about the lifestyles of many of the residents. Some would only experience any social interaction at mealtimes and would only get a visit from family twice a year, if that. Reduced mobility meant that the winter months would be spent awaiting summer, when they could go into the garden, which gave them a limited view of the outside world.

Similar to my influence there, schemes to allow children to visit would bring the vibrancy and the effervescence of the outside world to them. Channel 4 did a similar social study regarding this topic in their show Old People’s Home for 4 Year Olds. It showed that by the end of the time period, the introduction of children into the home on a regular basis had encouraged exercise, participation and activity of many of the elderly people.

Obviously, this scheme would have to come with the regular caveats, such as an opt-out basis, parental permission and regular health and safety checks to ensure the participants’ safety, but it wouldn’t just be the elderly who benefit. Children could learn an entirely different outlook on life and any knowledge passed on to them would help them (two years in a care home did me a world of good).

This scheme would embody Britain at its best, generation looking after generation, recreating society as a whole, rather than as a set of fragmented parts under the vague banner of a nation. This type of get together would, I hope, be another way to reunite communities in the spirit intended by the brilliant Jo Cox.

Jack Ashton is a Labour activist and student at the University of East Anglia.

More from LabourList

EXCLUSIVE: Usdaw General Secretary writes to PM ‘frustrated’ regarding changes to Employment Rights Act

Think tanks and MPs call for targeted response as Iran war impacts cost of living

‘This Labour Government needs to fix the Tory student loan fiasco’