Hundreds of thousands of people were shockingly killed in the genocides that engulfed Rwanda and parts of Bosnia in the 1990s. The horrors that took place compelled the world in pledging “never again”. Yet two decades later, history has repeated itself in Syria. Conflict there has completely devastated the country, with over half a million deaths and dozens of chemical weapons attacks. Some 13 million people have also been displaced and years of fighting led to a global refugee crisis on a scale not seen since the Second World War.

Jeremy Hunt has now all but officially conceded defeat in efforts to remove Bashar al-Assad from power. This will be an incredibly difficult pill to swallow for all those who have suffered or lost loved ones under his reign of terror. The foreign secretary also called on Russia to secure peace in the country and to make “sure that President Assad does not use chemical weapons”. That same Russia, though, has vetoed 12 UN Security Council resolutions on Syria, including those to investigate and to hold those carrying out chemical weapons attacks responsible.

This depressing outcome is no accident. In fact, it could have been avoided if not for our shameless failure to uphold the Responsibility to Protect commitment (R2P). This doctrine asserts that states have a responsibility to protect their citizens and others around the world from mass atrocity crimes. It was universally agreed at the 2005 UN World Summit and provides a framework for preventing atrocities of the kinds witnessed in Syria.

The first says states have a responsibility to protect their citizens from mass atrocity crimes. The second encourages the international community to help states fulfil this obligation. And the final pillar, asserts that if states are manifestly failing in their obligation to protect their peoples, then the world can use various diplomatic, political, humanitarian, and as a last resort and only if approved by the UN Security Council under strict criteria, forceful measures, to prevent mass atrocities occurring.

The R2P doctrine was successfully invoked by the Council in 2011, when the then Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi threatened to show “no mercy” against the country’s second city of Benghazi. But what was initially billed as a response to prevent an imminent humanitarian disaster, was in the end seen by China and Russia as a cover for wider regime change by NATO – something they would never countenance.

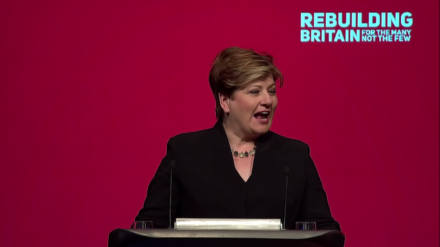

Ever since then, R2P has effectively been in a state of paralysis with the UN Security Council failing to take any meaningful action in response to the Syrian and Myanmar crises. It is for this reason that the Shadow Foreign Secretary Emily Thornberry declared last year that R2P was “on life support”.

It’s important to stress that the failures of R2P should largely be seen as failures of the UN Security Council and power play politics. But we cannot allow this vital humanitarian doctrine to wither away due to the Council’s intransigence. We need to think boldly about how we get R2P off of life support and make it a meaningful promise to all the vulnerable people depending on it around the world.

There are three things we could do. First, we need a more balanced assessment of the costs of action and inaction when facing these crises. Syria has tragically shown us what can happen if we fail to act properly or do nothing. Between the first peaceful protests in Syria in February 2011 and full-scale conflict in mid-2012, there was a huge missed opportunity for meaningful political and diplomatic action to help bring about a peaceful settlement. Being absent from the game eventually paved the way for Russia’s entry into the war to save Assad.

Yes, actions have consequences, sometimes dire. But we must remember inaction can also have tragic implications. Developing a cross-governmental atrocity prevention strategy would go some way to facilitating a more balanced assessment when facing a crisis situation.

Second, we must remember R2P is 99% about prevention. That means working towards developing a global early warning system with real teeth, which measures risk levels and identifies potential flashpoints. It means focusing our overseas support budget on capacity building in vulnerable states, such as developing robust judicial and rule of law systems. And it also means being there to help during big change moments, such as elections and transitions of power.

Preventative action doesn’t usually make the headlines and is difficult work. But it is the surest way to stopping atrocities ever happening, with Myanmar a textbook case. All the warning signs were there for years. But the international community turned a blind eye to the plight of the Rohingyas and other minorities in favour of the perceived bigger prize of the move to civilian rule. That was a fundamental mistake, which ultimately led to thousands dying and a genocide, that still continues.

If we are to reinvigorate the responsibility to protect doctrine, we need to think of it more as a ‘responsibility to prevent’. Finally, we need to ensure the UK is in no way, either directly or indirectly, playing a part in atrocity development. We could start by immediately ending arms sales and military support to states such as Saudi Arabia, who are bombing the life out of Yemen. If we are serious about atrocity prevention and still want to manufacture and export arms, then that trade must be properly regulated under an ethical framework.

Rayhan Haque is convener of the Fabian international policy group and will be chairing a panel at FEPS-Fabian New Year Conference: Brexit and Beyond on 19th January 2019.

More from LabourList

‘A third way approach is needed to protect children online’

‘Lammy’s jury trial cuts risk worsening racial bias in justice system’

‘Is there an ancient right to jury trial?’