Our climate has benefited from Theresa May’s shift into legacy mode, with her hugely welcome announcement that the UK government will follow the advice of the Committee on Climate Change (CCC) and legislate for a net zero emissions target. But she was pipped to the post by the devolved administrations: the SNP government in Scotland had already adopted a more ambitious net zero emissions target, while the Labour government in Wales pledged to achieve net zero five years ahead of the target advised by the CCC.

Game on. But, as the UK parliament recognised in its May 1st declaration, we face a wider environmental crisis beyond climate change – as if the latter weren’t terrifying enough. A few days after the debate, a colossal global assessment of humanity’s impact on nature made headlines with its finding that one million species are facing extinction.

The UK is one of the worst offenders, ranking 189 out of 218 countries for biodiversity intactness. That’s well below our neighbours Germany and France, and only slightly higher than the USA. And we know environmental damage isn’t only a problem for wildlife: the British public is becoming uncomfortably familiar with the perils of dirty air, polluted rivers, and the mental health costs of not being able to access green spaces. These issues often disproportionately impact the less well off.

People expect politicians to play their part

Faced with this relentless onslaught of depressing news, nearly 70% of Brits say they want urgent political action to address climate change and protect the natural environment, according to a recent poll. This week, thousands of people from across the country are participating in a mass lobby of parliament to tell MPs: The Time Is Now.

An astonishing 15,000 people intend to join the lobby. There is widespread agreement that something must be done to tackle all dimensions of the environmental crisis. The questions for political leaders can now be summed up as: what do you plan to do about it? And will you please get on with it?

Put environment at the heart of government

The practical solutions are out there: more trees, resource reuse, clean transport and so on. What we need now is to move the environment to the heart of government decision-making. That way, the necessary policies don’t depend on the fluke of having an unusually heavyweight politician in charge of the environment department, and this agenda will not be forgotten when political attention moves elsewhere.

The net zero emissions target is a good start, and now bold and legally binding targets must be enshrined in law for other policy areas too, including wildlife, waste and water. In doing so, the UK would be setting out a clear direction of travel towards environmental restoration. This can be achieved if accompanied by a robust set of institutions and mechanisms to track progress and to hold current and future governments to account.

Getting the legal framework right is necessary but not enough. Money will need to be spent. The shadow Treasury team is conducting promising work in this area, examining how sustainable economics can be embedded into the mainstream and conducting a review of the green book, which guides spending decisions. But perhaps the biggest test of commitment will be in handling competing interests. For all the Labour Party’s recent rhetoric around the climate emergency, that hasn’t stopped the vast majority of its MPs voting for a third runway at Heathrow. First Minister of Wales Mark Drakeford’s decision to cancel the M4 relief road partly on environmental grounds is an example of the hard-nosed decision-making required.

This political prize demands complete commitment

In private, there’s a degree of resentment within Labour about the number of green accolades gained by Michael Gove in his time at Defra, and the Conservative Party’s generous use of “world-leading” to describe every new policy announcement. To some extent, this is understandable. Your memory doesn’t have to be particularly long to remember the number of green policies scrapped or weakened during the Cameron government. Moreover, excepting net zero, the May government’s environmental impact on the statute book has in fact been negative. It’s perhaps unkind, but not unfair, of Sue Hayman to brand Gove as “minister for consultations”, as few of his announcements have yet been locked into law.

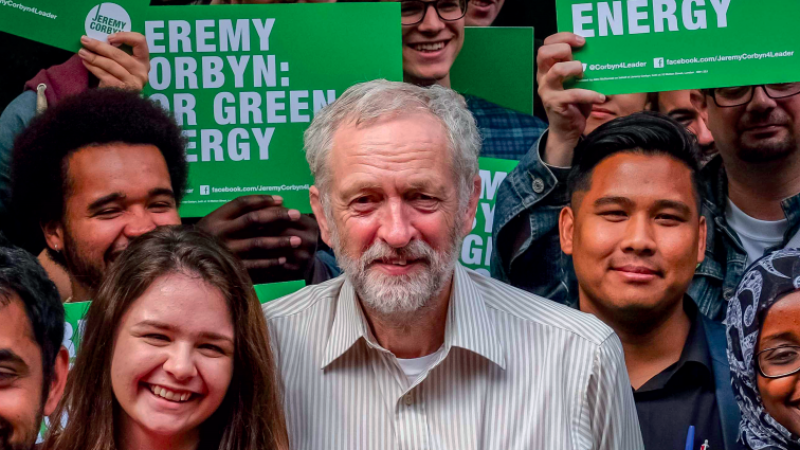

Yet neither of the two main parties in Westminster can claim to ‘own’ the environment as a political issue, with vital votes from green-minded millennials up for grabs. The challenge for Labour is whether it is prepared to make it a central part of its agenda – so far, Jeremy Corbyn has not devoted a single major speech outside of parliament to this topic, nor has he personally made it a central issue at PMQs. And it’s telling that, in the Brexit concessions May offered after weeks of negotiation with the opposition, the language on workers’ rights was much stronger than that on environmental protections.

As an environmental campaigner, it suits me to see political parties competing to be the greenest. But to have skin in this game, you have to keep the scoreboard ticking over and put all your top players on the pitch.

Amy Mount will be a speaker at the FEPS-Fabian Summer Conference on 29th June 2019.

More from LabourList

‘A third way approach is needed to protect children online’

‘Lammy’s jury trial cuts risk worsening racial bias in justice system’

‘Is there an ancient right to jury trial?’