For the first time in its history, Labour returned more women than men to parliament in the election earlier this month. What does that mean for the future of all-women shortlists?

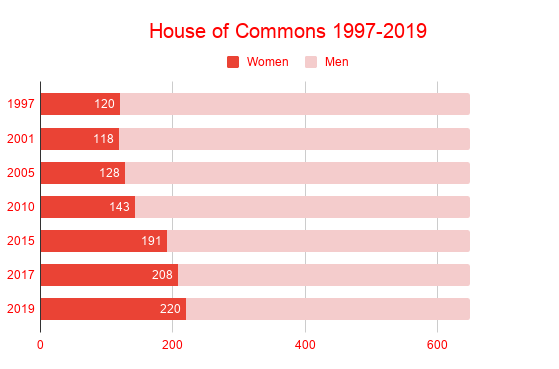

The parliamentary Labour party (PLP) now includes 104 women and 98 men; 45% of Labour MPs were women after the 2017 general election, and this has now increased to 51%. There are also more women overall in parliament than ever before, at 34% of all MPs – though of course this still doesn’t reflect the 51% of women that make up the British population.

Labour has used all-women shortlists (AWS) to select its parliamentary candidates for over two decades. And it’s proved to be an effective tool. But now the gender balance in the PLP has been levelled up, it has been argued that the party can get rid of the mechanism.

The practice has been frequently debated throughout its application within the party. Some have claimed that AWS is inherently discriminatory, or that it prevents the party from selecting the best candidate. Others have objected on the grounds that it’s patronising towards women.

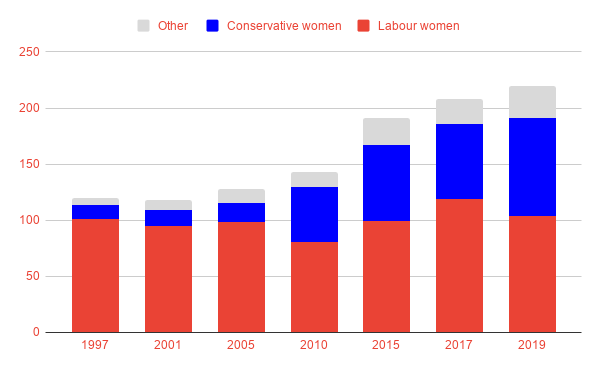

But in the 22 years that AWS have been applied to selections by the Labour Party, the number and proportion of women in parliament has increased dramatically. And the majority of the women elected have come from Labour.

AWS were first used in selecting candidates for the 1997 election, when the country saw a doubling of the proportion of female MPs in the House of Commons – from 9% to 18%. Since then, the percentage of women in parliament has stayed above 17%.

In 1997, Labour elected 101 women to parliament, while the Tories and other political parties elected 19 for a total of 120 female parliamentarians. Since then, the number of female Labour MPs has fluctuated but the proportion has been consistently higher than that of other parties.

This includes at the last election, in which Labour saw a large reduction in the overall number of its seats as the party lost 60 constituencies it previously held. Despite this, the party still returned more women than any other party, while less than a quarter of Tory MPs are women.

The continued use of AWS has been far from certain over the years, and it has often been considered a time-limited measure. The Labour Party adopted AWS for parliamentary candidates at its 1993 conference, but Tony Blair initially announced in 1995 that the policy would be in place for one general election only.

An industrial tribunal judgement in 1996 actually found that the practice was illegal and they subsequently weren’t used in selecting candidates for the 2001 general election. The number of female candidates fell as a result, and Labour went backwards – returning only 95 female MPs.

The Labour government then amended the existing legislation with the Sex Discrimination (Election Candidates) Act 2002, allowing the use of AWS by political parties for selecting candidates in various elections – including for parliamentary but also Scottish, Welsh Assembly and local elections.

The legislation originally included a ‘sunset clause’ that provided for the Act to expire at the end of 2015 – however, the Equality Act 2010 extended the statute so that it will now continue in effect until 2030. The life of the legislation could be extended again by a parliamentary order.

Labour has used the mechanism allowed under the legislation in selections to replace a woman who is retiring from parliament, and in 50% of all other seats, with the aim of achieving gender parity in parliament.

The Labour Party rulebook states: “The party will take action in all selections to encourage a greater level of representation and participation of groups of people in our society who are currently under-represented in our democratic institutions. In particular, the party will seek to select more candidates who reflect the full diversity of our society in terms of gender, race, sexual orientation and disability, and to increase working class representation.”

And in 2016, while giving evidence to the women and equalities select committee, Jeremy Corbyn committed to achieving 50% women’s representation in the PLP by 2020. Given the latest intake, then, it’s possible that the party might decide to dispense with the practice.

Regardless of what the party decides, Labour may have difficulties in continuing to use the mechanism anyway; the Equality Act 2010 states that the purpose of a selection arrangement, such as AWS, “is to reduce inequality in the party’s representation in the body concerned”.

Crucially, one of the examples in the accompanying explanatory document to the Act says: “A political party can have a women-only shortlist of potential candidates to represent a particular constituency in parliament, provided women remain under-represented in the party’s members of parliament.” It may be deemed unlawful to implement AWS – for parliamentary selections – in a party where the majority of MPs are women.

But the fact that Labour has more women in the PLP after the recent election, doesn’t mean the party won’t backslide if it stops using AWS – as mentioned, Labour saw a decline in both female candidates and MPs when it did so in 2001.

And it’s worth keeping in mind that, in absolute terms, the number of female Labour MPs really hasn’t increased much. True, the current proportion of female representation is high, but the 1997 election saw the party send only three fewer women to Westminster.

It’s clear that Labour’s use of AWS has had a significant impact on the number of women in parliament. But the overall representation of women in the Commons still lags far behind that of their male counterparts, and Labour’s reduced presence means that the impact of its own diversity on the chamber more generally is limited.

As we think about this, readers will be aware that Labour is about to begin the process of selecting its new leader. Several MPs have said the next Labour leader should be a woman, including the Shadow Chancellor John McDonnell. Labour has only ever had women as interim leaders, while the Tories have had two women elected to the top job.

The fact remains that while 51% of Labour MPs are women, only 34% of all those sitting in the House of Commons are. Our legislative body clearly has a long way to go. Now there’s a new challenge: the Equality Act may, given that there is a majority of women in the PLP, mean that the party has to look for a different way to achieve gender parity in parliament.

More from LabourList

Which ministers have done the most and fewest broadcast rounds in year one?

‘Welfare reforms still mean a climate of fear. Changes are too little, too late’

Welfare bill: Which MPs are still voting against reforms?