Four weeks into Labour’s leadership contest, and we have just over a third of Labour’s 648 Constituency Labour Party (CLP) nominations. This opens a window into the minds of party members. Lots can still change but we now have a good idea of what members are currently thinking and from where each candidate draws their support.

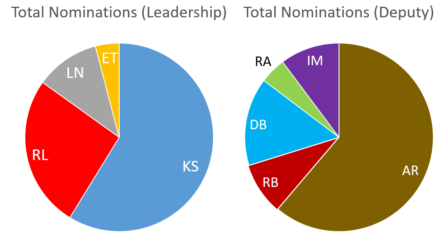

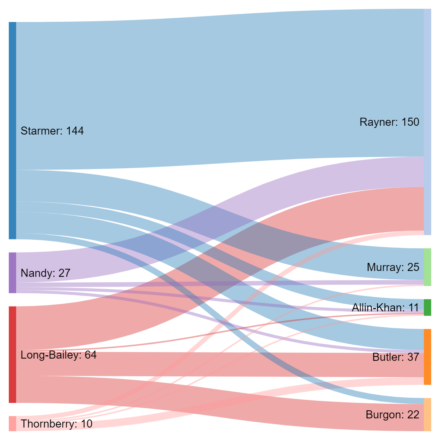

First, the headlines. If the remaining two-thirds of CLPs behave like this first batch then, on April 4th, Keir Starmer will be elected leader, and Angela Rayner his deputy. Each currently has approximately 60% of nominations in their respective contest, with their nearest competitor trailing some way behind.

But from where do the candidates draw their support?

From 2015 to 2020

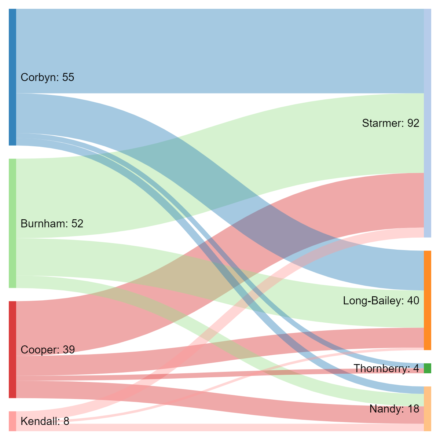

Comparison of 2015 and 2020 nominations paints a complex picture. Rebecca Long-Bailey is sometimes described by the ‘continuity’ candidate and has the endorsement of Corbynite organisations like Momentum and the Campaign for Labour Party Democracy (CLPD). But in terms of CLPs, her support from those nominating Corbyn in 2015 is roughly the same as from those that nominated Andy Burnham. Put simply, her reach in 2020 is not the same as Corbyn’s in 2015.

By contrast, despite vocal support from prominent critics of Corbyn’s leadership, Starmer has nonetheless won the majority of Corbyn’s 2015 nominations so far. There is lots of churn in the party membership but the figures make it almost certain that Starmer is picking up lots of Corbyn supporters. There is, perhaps, more overlap to the two politicians’ appeal than first meets the eye.

Other trends are more predictable. Ian Murray is unashamedly vocal in his criticism of the current leader, claiming in 2017 that Corbyn was “destroying the party”. His nomination patterns reflect this: almost half of his CLPs nominated Liz Kendall in 2015, compared to only a tenth that nominated Corbyn. This suggests his support has a fairly low ceiling: Corbyn remains popular with the membership and the most successful candidates recognise this.

Location, location, location

If each candidate’s position on Labour’s internal political spectrum only partially explains their support, what are the other factors?

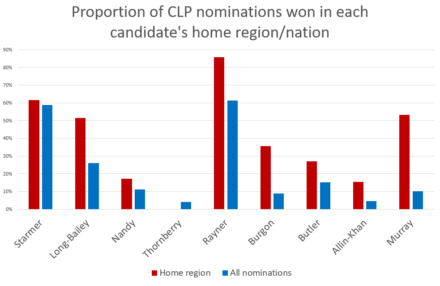

Local reputation seems to trump factional loyalties. All candidates perform better in their home region or nation than they do overall. Richard Burgon and Ian Murray enjoy over four times the support in their respective regions as they do nationally. The exception is Emily Thornberry, who has won no London nominations. That said, she shares a home region with the frontrunner – Starmer, who represents a neighbouring constituency in north London – and doesn’t have many nominations in general (sorry Emily!). It should be noted that she launched her campaign in her home town, Guildford, and has been targeting seats in the South East instead of London.

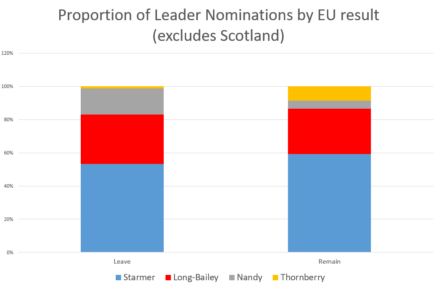

How do areas that voted Leave compare to those that voted Remain? Starmer’s critics say the Shadow Brexit Secretary will have no appeal in Leave-voting seats. I won’t comment myself, but it’s clear that party members in these areas disagree: half of them have nominated him. That said, this is nonetheless lower than in Remain areas.

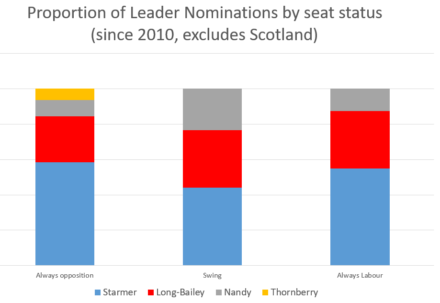

Brexit plays a part in others’ support too. Thornberry’s nominations are almost exclusively from Remain areas, while Lisa Nandy draws the bulk of her support from areas that voted Leave. Long-Bailey enjoys significant second-place support in both types of seat but performs slightly better in areas with a Leave vote. She also scores a little higher in seats which we held at some point since 2010, but again is second place to Starmer. Seats which Labour have not held in this period provide all of Thornberry’s nominations. Seats which have changed hands since 2010 make up one of the few categories where Starmer does not have a majority.

Leader and deputy

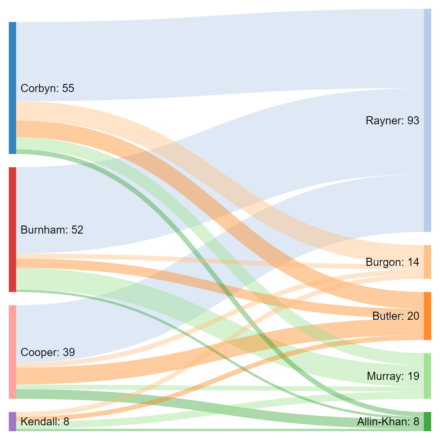

The relationship between 2015 and 2020 nominations are muddied by membership turnover. There is no such problem when we compare nominations for leader and deputy: the decisions are taken at the same meeting.

Starmer’s supporters seem to divide between the deputy leader campaigns at roughly the same rate as the total, albeit with Burgon under-represented. Lisa Nandy’s nominations, by contrast, are almost always coupled with a nomination for Rayner.

There is only one joint ticket in this election and there is no way you’d guess it from the nominations. Despite their mutual endorsements, fewer than half of Long-Bailey’s CLPs have nominated Rayner, and fewer than a fifth Rayner’s have returned the favour. In so far as the mutual endorsements have made a difference at all, it seems to have been more to Rayner’s benefit than Long-Bailey’s.

Reports of the Labour left’s death have been greatly exaggerated

There is a section of the Labour membership who will consistently support the ‘official’ left candidate. This cohort is significant but a minority nonetheless. Any illusion otherwise was created by Corbyn himself: an extraordinary candidate who could only transform the fortunes of the British left because he had appeal beyond it. There is a layer of Labour members who are open to supporting the hard left but who will not do so automatically. They voted for Corbyn but many have switched to Starmer or even Nandy. Long-Bailey can still win if she finds a way to appeal to these members. I hope she does.

Nomination results thanks to @CLPNominations.

More from LabourList

Economic stability for an uncertain world: Spring Statement 2026

‘Biggest investment programme in our history’: Welsh Labour commit to NHS revamp if successful in Senedd elections

James Frith and Sharon Hodgson promoted as government ministers