A staggering 580 of 648 constituency Labour parties (CLPs) have now nominated candidates to be the next Labour leader and deputy – more than in any contest before. A few may trickle still in before the Valentine’s Day deadline, but not enough to make any real impact.

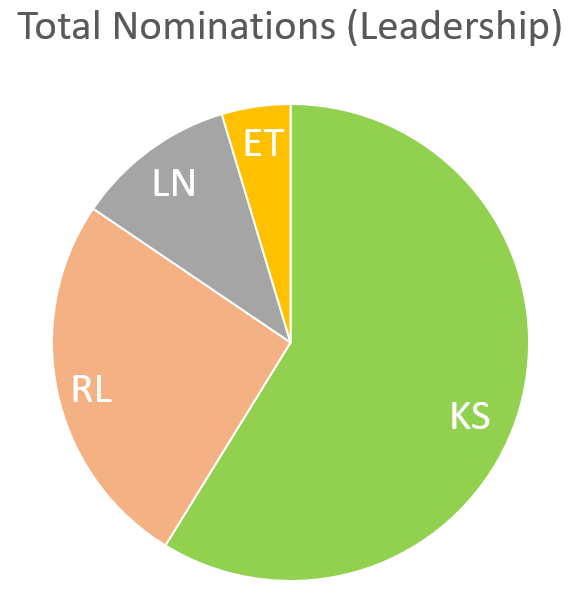

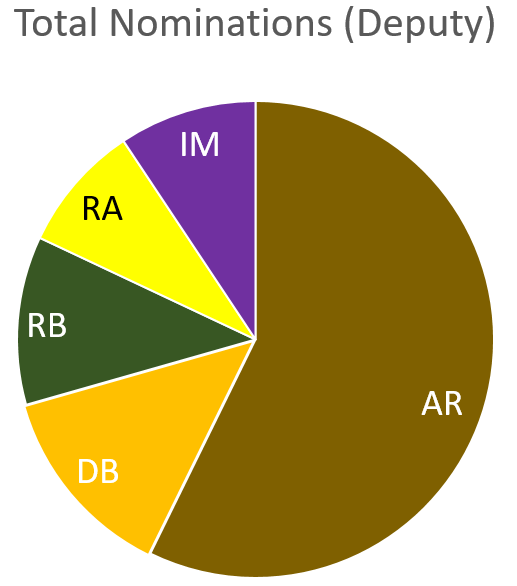

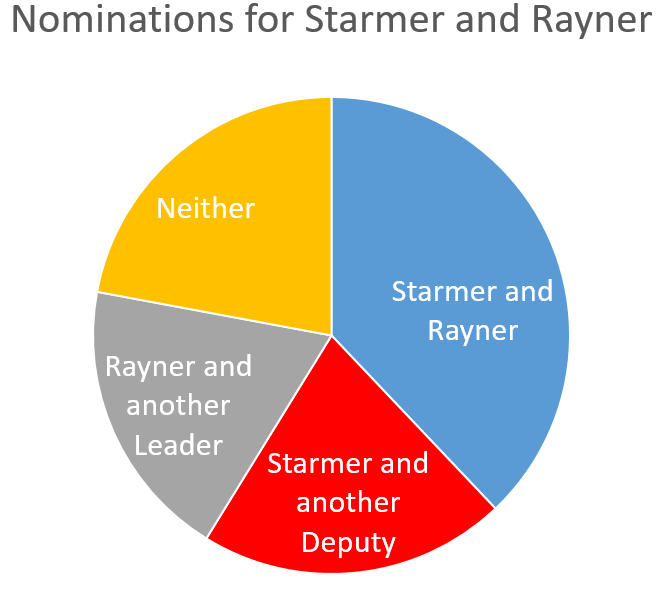

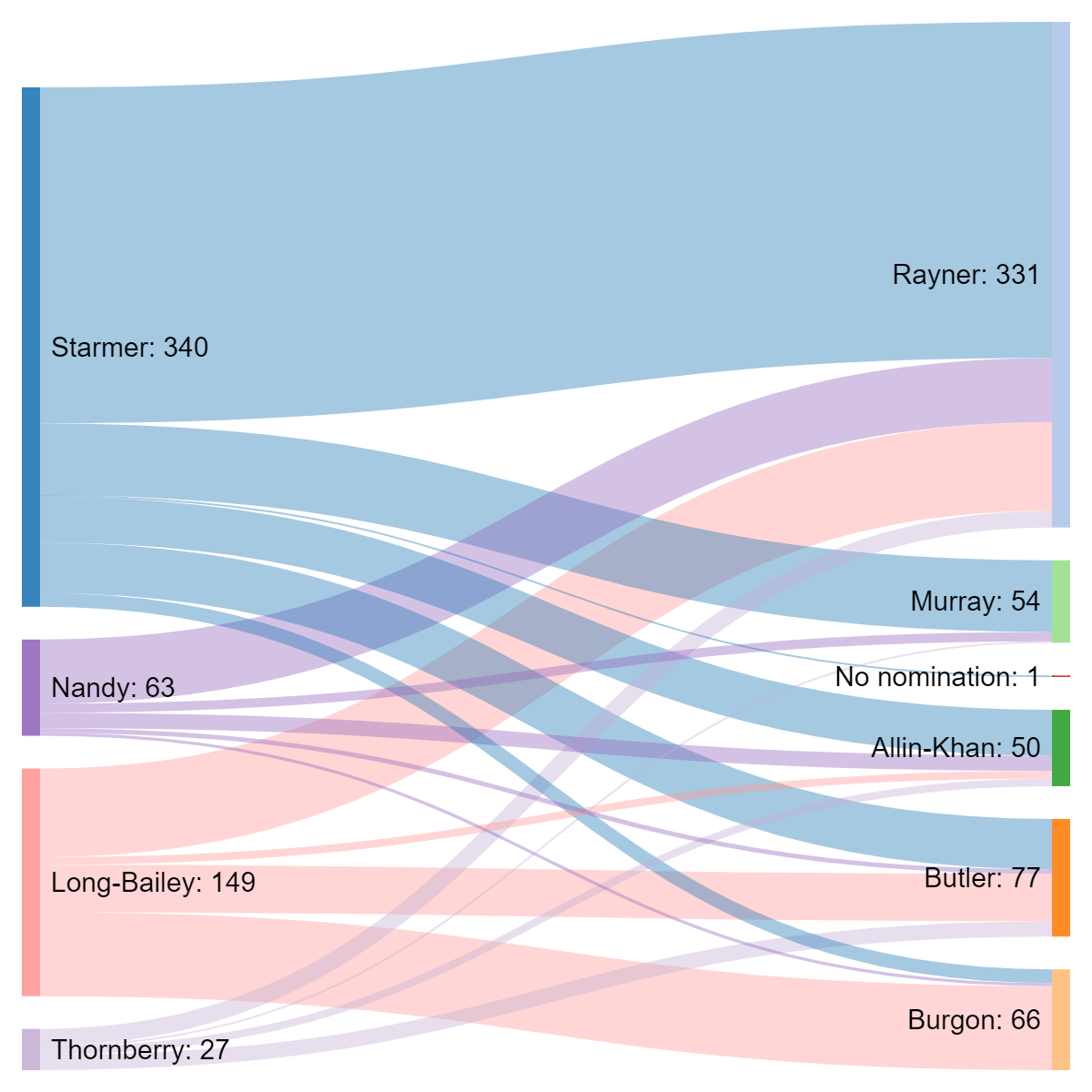

Just over a week ago, I analysed the results from the first 250 CLPs. The total number has now doubled. What’s changed and what has stayed the same? The headlines have not changed. Keir Starmer and Angela Rayner are in the lead by a considerable margin. Each has approximately 60% of nominations. Two in five CLPs have nominated both candidates, one in five have nominated each one alone, and only one in five have nominated neither.

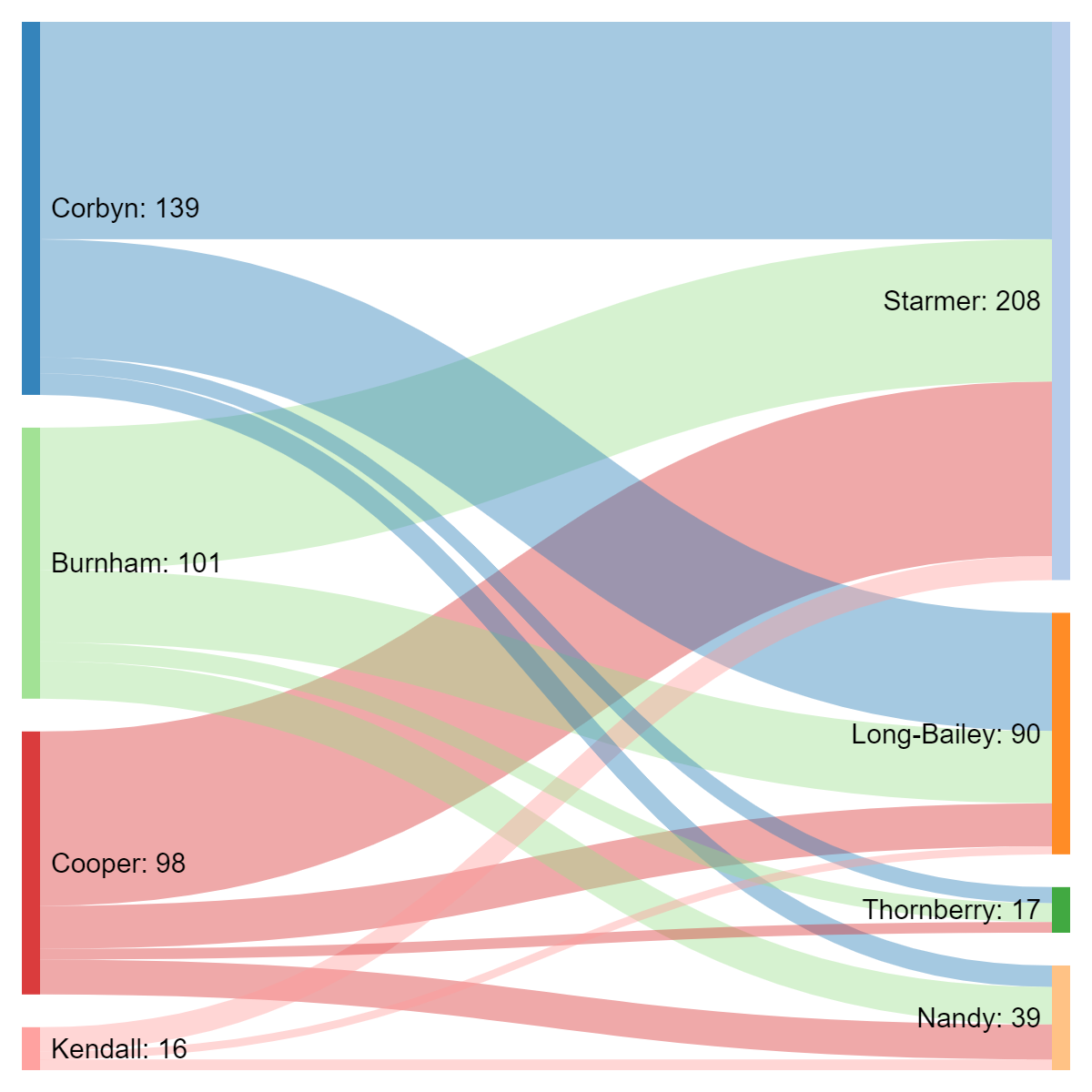

There have been subtle changes to the underlying patterns. First, let’s look at the relationship with 2015 nominations.

Where does each candidate find their support?

Starmer’s support is still spread roughly proportionately across the four candidates from that contest; he has a majority from each. Rebecca Long-Bailey performs considerably better amongst CLPs that nominated Jeremy Corbyn or Andy Burnham than she does with ones that opted for Yvette Cooper or Liz Kendall. Less than a fifth of Lisa Nandy’s nominations come from CLPs which nominated Corbyn in 2015, despite him winning the most in that contest.

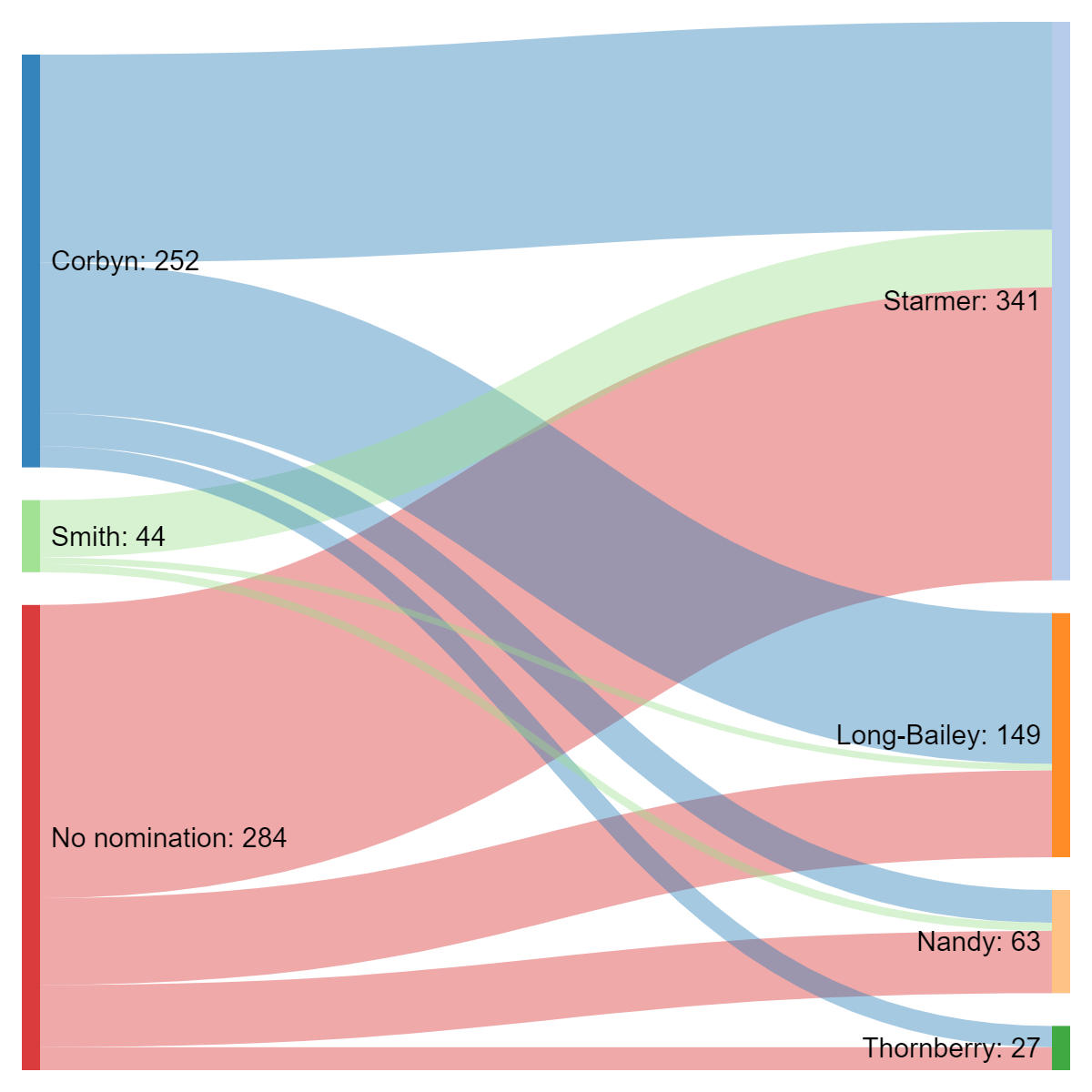

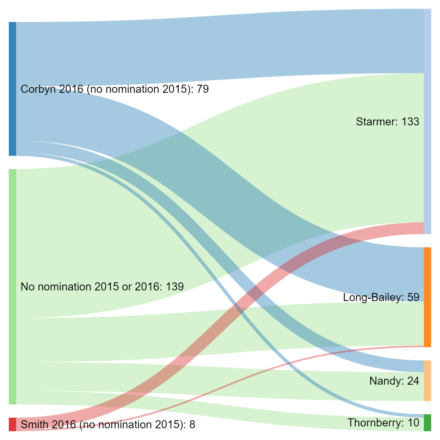

The relationship with nominations from the 2016 leadership contest is more stark. After all, that race was essentially a referendum on Corbyn’s leadership – Owen Smith was never more than a placeholder.

CLPs that nominated Corbyn are divided. The majority want Starmer, but Long-Bailey is a strong second. By contrast, those that nominated Smith favour Starmer over Long-Bailey by a margin of seven-to-one. CLPs will have changed a lot but the fault lines set in the summer of 2016 still have meaning today.

What about the relationship between nominations for leadership and deputy? The patterns from last week have only become clearer. The Momentum-backed mutual endorsements of Long-Bailey and Rayner have meant almost nothing. Only 59 CLPs have nominated both: this is a third of Long-Bailey’s nominations and just a sixth of Rayner’s. The Campaign for Labour Party Democracy (CLPD) joint ticket of Long-Bailey and Burgon has almost as many, with 55 nominations.

CLP and PLP unity?

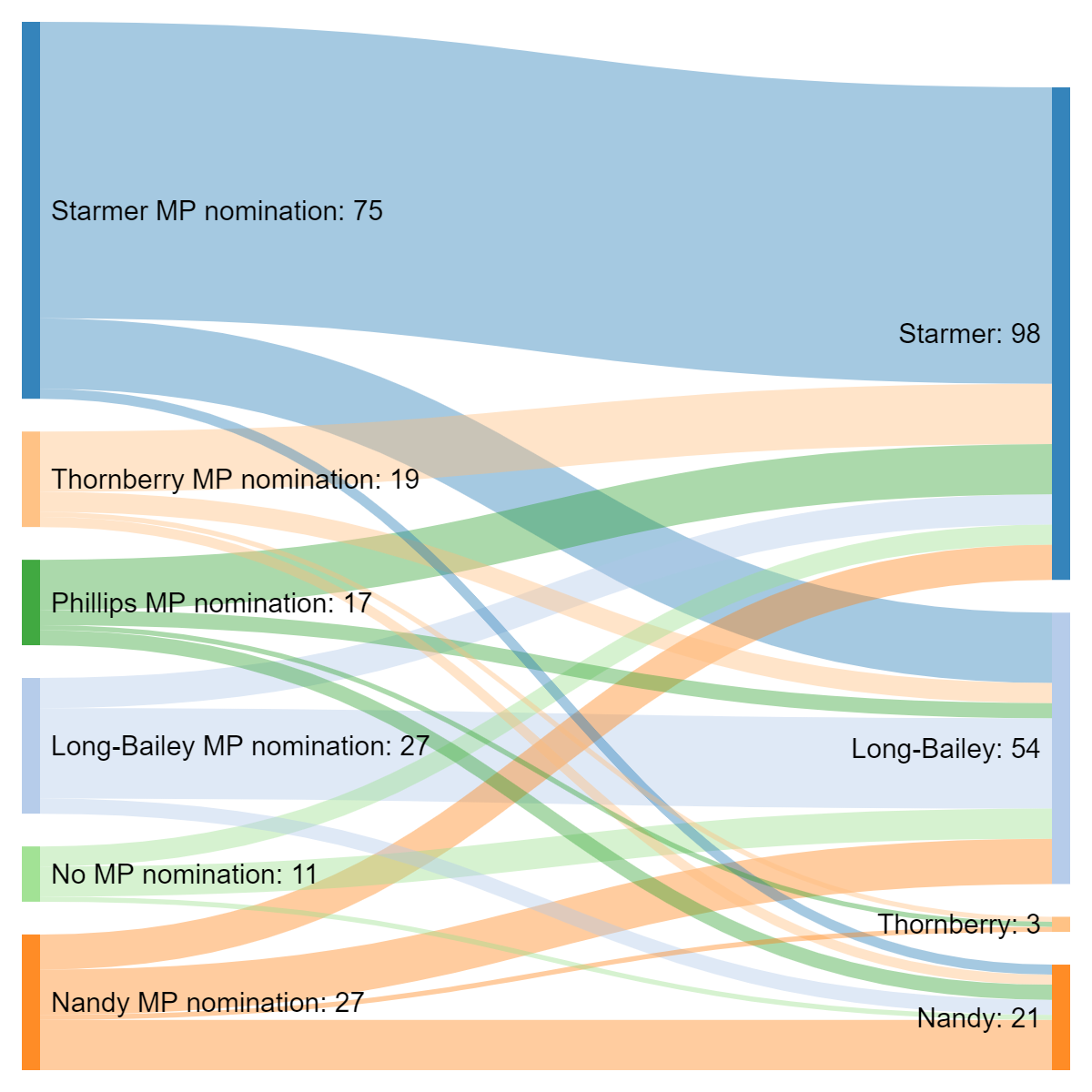

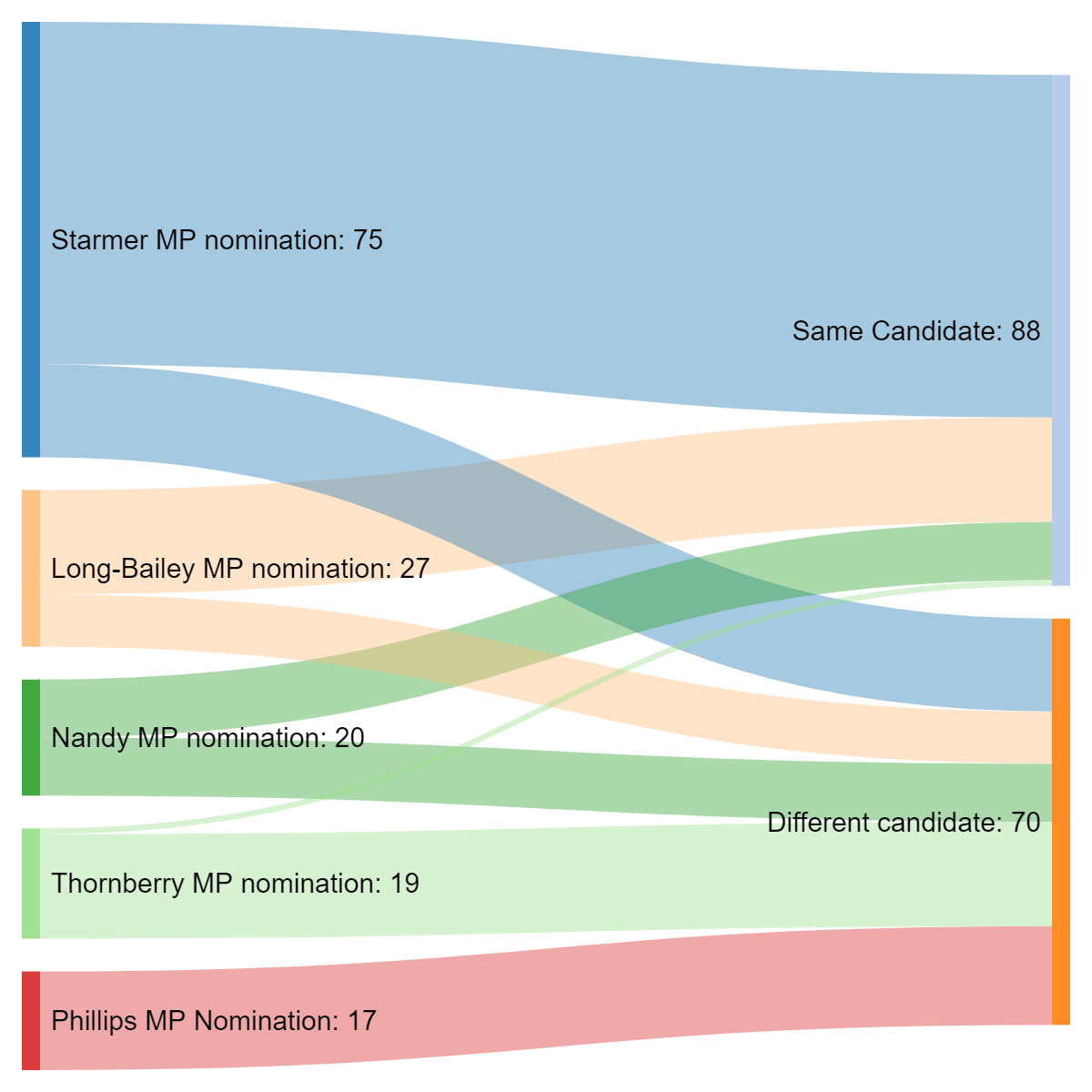

A new thing to look at is how MP nominations match up with that of their local CLPs. A defining feature of the last four years was the accusation that MPs are out of touch with their local parties. This was driven in large part by their divergence on the 2016 election: MPs overwhelmingly backed Smith, while CLPs overwhelmingly supported Corbyn.

In 2020, that has changed. In most Labour constituencies, the MP and local party have nominated the same candidate. The exception is Thornberry’s nominations – many of her MPs nominated her to ensure she reaches the ballot, and widen the debate. CLPs have not been so kind: most of her nominations are from constituencies with no MP.

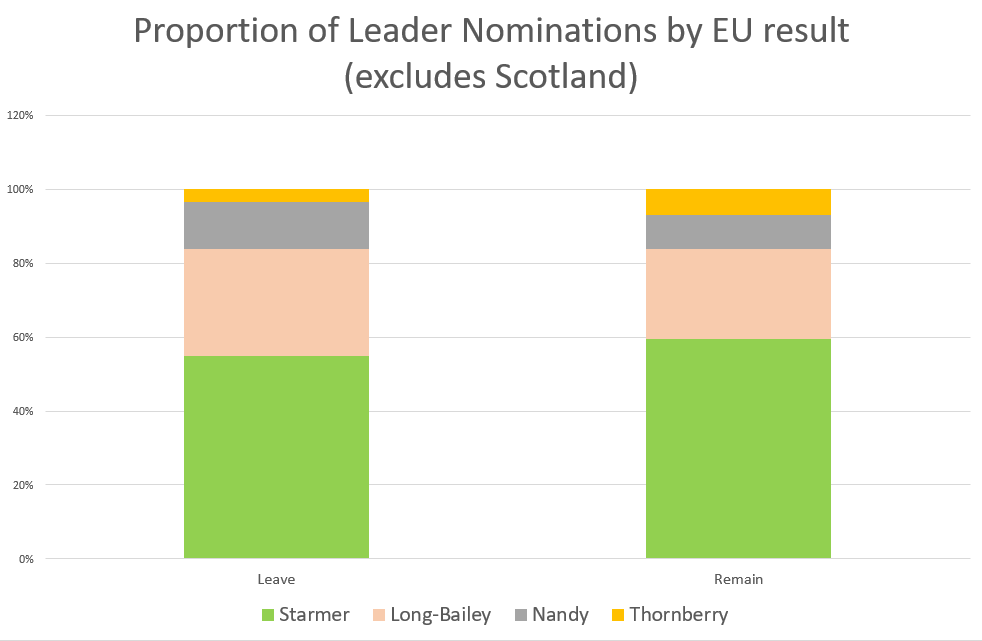

What about different types of seat? Perspective on the EU is still a factor. CLPs nominating Starmer and Thornberry are more likely to be in areas that voted Remain, while those supporting Long-Bailey or Nandy more often voted Leave.

Nonetheless, the Brexit vote does not disrupt the headline results: Starmer has won a majority of both groups, Long-Bailey is in second place, and Nandy is beating Thornberry to third place. Perhaps we’re not so divided after all.

Newly active CLPs

There are two hundred CLPs that did not nominate in 2015 but have done in 2020. Just over a third nominated in the 2016 leadership contest between Corbyn and Smith. All but one of those that nominated Smith have now nominated Starmer, whereas those which nominated Corbyn are split almost equally between him and Long-Bailey.

By contrast, those which did not nominate in 2015 or 2016 are more likely to have nominated Starmer than the average. A clear pattern has emerged: in 2016, parties that had become more active under Corbynism rallied to defend him, whereas those which have become active more recently have flocked to Starmer’s banner.

Who will win?

The message is very clear. Seven out of nine candidates will be keen to play down the extent to which these nominations are representative of their support in the party. Unfortunately for them, nominations tend to be a very good test of each candidate’s popularity. However, the nature of the system – where each CLP is a winner-takes-all contest – exaggerates the differences.

It is unlikely that the final result will be the landslide those figures suggest but, in the leadership race at least, I suspect that they will at least reflect the same order. The race for deputy is more complicated because four of the five candidates have a similar number of nominations.

Nominations predicted the order of results in 2015, and in 2010 it came pretty close. In a two-candidate contest, you can go even further and predict the numbers using a handy formula. CLP nominations in the 2016 leadership race predicted that Corbyn would beat Owen Smith 64% to 36%. In the end, the result was 62% to 38%.

It is all but impossible that Starmer and Rayner will lose. Moreover, their staggering leads make it clear that they have hoovered up support from both previous Corbyn supporters and his critics. Is this a new era of unity? A happy compromise between those who want the Corbyn project to enter a new stage, and those who want it to end? Or rather, will the expectations for the new leadership be ultimately irreconcilable? Only time will tell.

More from LabourList

Economic stability for an uncertain world: Spring Statement 2026

‘Biggest investment programme in our history’: Welsh Labour commit to NHS revamp if successful in Senedd elections

James Frith and Sharon Hodgson promoted as government ministers