“My mum always used to tell us she was walking home through Walsall one night as a pregnant woman and was attacked in the middle of the street. Other people could see what was going on as these men attacked this pregnant woman and called her all sorts of racist names. They nearly killed her and they nearly killed her child, which was me.”

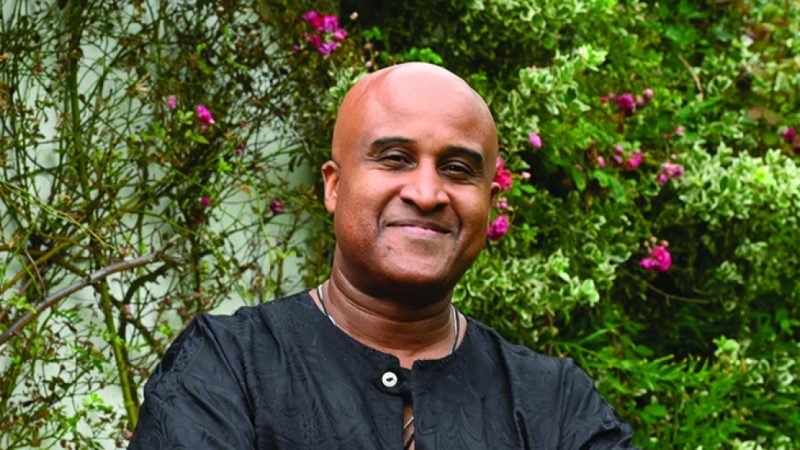

It becomes evident as we chat over Zoom that racism has affected every part of Roger McKenzie’s life. The candidate to be UNISON’s next general secretary was always aware of its lethal consequences. “Being anti-racist wasn’t some badge you could take off,” he tells me. “For me and my family, it was literally a matter of life and death.”

“As a child, I was having to fight my way to school every morning,” McKenzie says. “We didn’t have far to go, as it was only a ten-minute walk to school, but I was having to fight, not just name-calling but physically.” At the end of the day, he would fight his way home again – “sometimes to find racist slogans daubed on our wall, sometimes having to deal with dog mess and sometimes petrol bombs thrown through our letterbox”.

McKenzie was born in 1960s Walsall on the outskirts of Birmingham, in a region that has a long and painful history with racism. Walsall is just a few miles from the town of Smethwick, which became infamous after a Tory candidate won the constituency in the 1964 general election using the slogan “if you want a n****r for a neighbour, vote Labour”.

Traditionally a Labour-supporting area, ‘Red Wall’ cities in the West Midlands such as Stoke were some of the first to elect councillors from the fascist British National Party. On returning to the region later in his life, McKenzie describes how walking through the town of Tipton, near Dudley, he saw BNP posters brazenly displayed in people’s window, something he’d “never seen before”.

His first day at primary school was mere months after Enoch Powell’s infamous ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech, and national events such as that “shaped a lot of the attitudes and behaviours” of those around him. Even the launch of TV show Roots, which depicted Black people resisting slavery in the US, had terrible effects. “We got a lot of pride from that show as there weren’t too many stories around about our history,” he explains. “But what it also did was ignite a load of racism against us, that we had to deal with in school.”

Later on in his schooling, he recalls asking a careers officer whether he could become a journalist in future, only to be told that “Black people didn’t do those jobs”. He was asked about joining the Army instead, or the airforce – “not to fly aeroplanes mind, but to fix them,” McKenzie adds. Fighting constant racism in school with other Black pupils, he learned it was much easier when they stood together. “That’s where my beliefs about how you challenge inequality and injustice come from,” McKenzie explains. “That you can try and fight your way individually against these things, but we’re far more able to succeed if we are able to fight collectively.”

After leaving school at 16, his dad took him into the front room, the “posh room” of their cramped terraced house, and told him to join a trade union the moment he started work. His father was a railway worker for 30 years and consistently a member of the National Union of Railwaymen, now the RMT. “That’s where some of my values start from. From family members who were all staunch trade unionists and Labour supporters to the core.”

McKenzie left school on a Friday, started work as a painter-decorator the next Monday, and by Tuesday was already the subs collector for the union. “My job was to go around on a Friday afternoon when people had just got their pay packets and persuade them to give me some money for the union,” he recalls. “That was not one of the most successful jobs I’ve ever done, but I learned new forms of abuse in that time, and also how to duck and dive out of the way of bricks being thrown at me.”

That job disappeared after Margaret Thatcher took power, McKenzie tells me. He then became a housing officer at Walsall Council, and immediately joined the Labour Party and the National Union of Public Employees (NUPE) that would later merge to form UNISON. This period at Walsall Council was defined by political radicalism, as the local authority worked to decentralise council services. The council leader was “eventually expelled from the Labour Party, frankly for being too left-wing,” as McKenzie puts it, but he had served as a “great mentor”. From then, McKenzie was set on being a lifelong trade unionist.

His first foray into union education, a field he would later specialise in, came after he was asked to do shop steward training for NUPE. After leaving school with two O-Levels, returning to the classroom was not something that appealed to McKenzie. “I remember going to this training place in Walsall and I remember turning to walk away, thinking ‘I’ll give this a wide berth’,” he recalls. “Then I bumped into this guy who it turned out was the tutor and he persuaded me to come back in.”

The first course opened his eyes: “I felt for the very first time really that what I thought about something had some value. I had spent most of my life being told that stuff I thought was important wasn’t.” Eventually, he became a union educator himself after getting “tricked into teaching on courses”, as he puts it. He moved to Manchester to teach at the then Central Manchester College, before later taking another teaching position in London.

It was in London that the current assistant general secretary first became actively involved in the Labour Party as a constituency secretary and local councillor in Islington. “I’ve been a member of the Labour Party since 1981, and there’s been only one of the leaders during the whole time that I’ve been a member that I could absolutely say I was a big supporter of, and that’s Jeremy Corbyn.”

How does he feel about the new Labour leadership? “We will always give support to the party, as far as I’m concerned, but we want to see some evidence of a continuation of direction,” McKenzie tells me. “It’s about demonstrating that Labour is going to continue to stand up for public service workers.” He does admit that he has been worried about the recent abstentions by Labour and “they should have opposed the government and made things really clear”.

McKenzie speaks endearingly about deputy leader Angela Rayner – “a really, really good friend of mine” – who spent years as a UNISON organiser before standing as an MP. He thinks more members should follow in her footsteps. “My basic attitude is that we have to take the union into the Labour Party, rather than the other way round,” he explains. “There are far too few UNISON members taking an active role in the Labour Party and I think we’re losing an opportunity to take our policies and our values into the party.”

Asked about his view of Unite recently choosing to reduce its Labour donation, McKenzie says: “What I would like to see is more UNISON members taking our message into Constituency Labour Parties (CLPs) and influencing the direction that the leadership is going… I don’t think you do that by withdrawing, I think you do that with more engagement.”

McKenzie became the first Black national education officer of a UK trade union when he left his teaching role to join the National Union of Civil and Public Servants (NUCPS). After the death of Stephen Lawrence, he moved on to become the TUC’s race equality officer and helped draft new rule changes for the trade union federation. “Frankly I was amazed it wasn’t already a requirement of affiliation to the TUC that you had to demonstrate a commitment to equality,” he says. McKenzie later served as a regional officer for his native West Midlands, both at the TUC and subsequently UNISON, before being made assistant general secretary of the public service union a decade ago.

The trade union movement still has a lot more to do to root out racism, McKenzie makes clear. “If you’re Black, you know what’s going on,” he says. “Racism is the other pandemic that’s taking place, it’s the second pandemic and it needs to be treated with the same seriousness as coronavirus. And we have far too much evidence that it’s not at the top of people’s agenda.”

As a member of the TUC general council, McKenzie has helped set up a new task force on racism. “But it’s a bit sad that we actually have to set up another task group to look at stuff that should just be an ongoing part of a trade union’s work,” he says. His key pledge, to increase the number of UNISON activists and increase engagement, is key to tackling that racism. “You tackle racism with solidarity, with collectivism. And that’s what I want to see. All of our members making it clear that they will not be divided in the workplace against each other.”

What does McKenzie have to say to those who argue that his leadership role makes him part of the UNISON establishment? “I think it shows absolutely a complete disregard for what it takes for a Black person to get anywhere within the trade union movement. I find it quite disgusting actually,” he replies. “From people who refuse to stand up for Black workers or just discovered racism so they can stick on a Black Lives Matter badge as if it’s the latest fashion. Never marched against the fascists. Never had letter bombs thrown through their letterbox. Never been spat at in the street. Never had eggs thrown at them. As I have, all of those things.”

“All of a sudden, I’m establishment. I mean, when does establishment begin and end?” He ponders. “At what point do you stop being working-class, do you stop being an activist? Because I’ve never stopped being an activist of any kind.”

More from LabourList

‘Is there an ancient right to jury trial?’

‘To tackle the housing crisis, the Treasury must rethink how it values social housing investment’

‘Labour action on extreme poverty can stop voters going Green’