While everyone naturally enjoys the Prime Minister’s meltdown, time and attention is being deflected away from serious alternatives to the mess that the Tories and the country are in. I keep thinking about New Labour, how it won and its legacy. Not just because 25 years later Tony Blair keeps popping up with advice for whoever is listening, or because he has apparently anointed Keir Starmer as his heir. Nor because there seems to be, on the face of it, many parallels between then and now.

No, my mind keeps returning to 1997 for two reasons: first, because New Labour puts current, or Now, Labour in the shade; and second, because despite how impressive it was, the New Labour project ultimately failed. While there are things to learn from that era, a pale imitation of something that left us where we are today feels like a wrong move.

Let’s unpack that, starting with the obvious similarities. After four straight wins, a Tory government is in turmoil, mired in sleaze, a competent centrist Labour leader is keen to win and there are even Tory MP defections. But that’s where the similarities end.

Then, the Tories had a wafer-thin majority; this time, their fourth win was their biggest and they command the Commons. Then, they had already made the switch to a new leader who had won in 1992; this time, they have the switch in the bag, and if they make it, it could be the change the country feels it needs, helping them to a record fifth win in a row. And now Labour’s electoral mountain is far higher. The party needs 124 seats for a majority of just one, against an electoral system so skewed in the Tories’ favour, Labour needs a 12% poll lead just to win so narrowly.

Much bigger things have also changed since 1997. Climate is now the systemic issue facing the planet. New Labour came to fruition in benign economic circumstances, on the wave of 60 consecutive quarters of growth. They never accounted for the 2008 crash, nor its austerity aftermath. Now, after Covid, the economic conditions are perilous and remain so without a radical economic rethink that looks light years off.

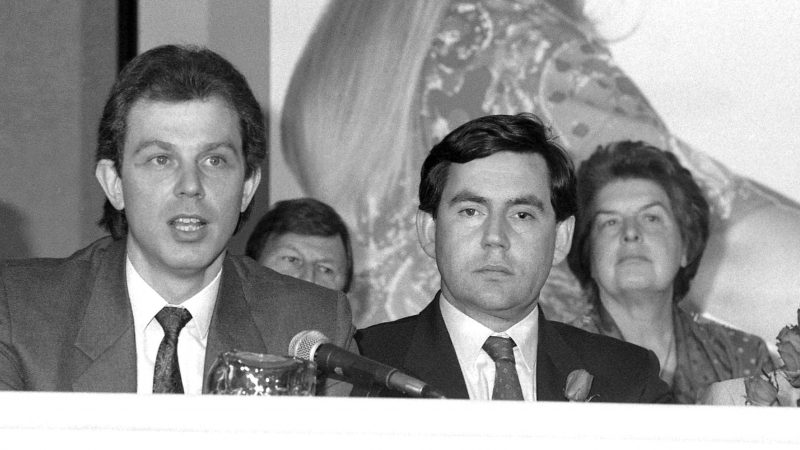

But here is the big political difference facing Now Labour. New Labour, whatever you think about where it ended up, was a serious political project. I should know, I was a small cog in its wheels, having worked for Gordon Brown and then Peter Mandelson during the 1997 campaign. It had intellectual heft delivered by Anthony Giddens, policy and ideas from the likes of Will Hutton, Charlie Leadbeater and Julian Le Grand, as well as new think tanks it encouraged like Demos; a state craft in the form of the new public management; a political economy based around supply side reforms; a message that relentlessly contrasted itself to Old Labour; a shadow cabinet full to the brim with talent, from Robin Cook to Mo Mowlam; and ruthless centralised control.

New Labour had a convincing story of national renewal. Labour today is but a shadow of that project, in a world that has moved on by much more than a quarter of a century. That moment cannot be repeated because the conditions for repetition have long gone. Today, if Labour is up in the polls, it is largely because the Tories are down, and so is easily reversible. While New Labour was daring and bold, Now Labour is a cautious, small target project, with the goal of falling over the line first. Even if that is remotely possible, then what?

Here is the killer. While New Labour was streets ahead of Now Labour, it still failed. Yes, it won elections and did much good, but it didn’t change the country in deep and abiding ways. The Tories, from 2010, easily swept its legacy away. Its mild technocratic reforms won too few strong supporters and left too many behind. At best, it took Old Labour for granted as it embraced full-throated financialisation and globalisation without putting in place the necessary social and economic backstops. This all helped bequeath not just the crash of 2008 and the austerity that followed, but the loss of Scotland to the SNP in 2014, Brexit in 2016 and the ‘Red Wall’ seats in 2019.

But as its adherents like to remind us, New Labour did win elections. And that’s why I was initially attracted to the project. You have to be prepared to connect with the majority. Being in office is different from being in power, though. They seemed to accept their late pollster Philip Gould’s insight that this is a ‘conservative country’. New Labour governed like they feared the country more than they wanted to change it, and through their timidity built a cage from their victory. The challenge now is to reconnect with a majority of the public but then help lead them to support and enact measures that make their lives and society better through necessary deep economic and democratic change.

Today, because of Covid and climate, the tech and care revolutions, the crisis of democracy and rampant inequality, and the threat of right-wing populism all this engenders, any successful progressive project must have the vision, policy and roots into wider social forces to create and sustain a transformative agenda. The good news is that there is a progressive majority, as every poll now shows – it just refuses to be corralled into Labour’s big tent like 1997, which enjoyed 20% plus poll leads. This majority can only be represented via negotiation between the progressive parties.

Labour might just win office by default, but will be less prepared for power than in 1997, and in circumstances much more challenging. Neither the planet nor progressive politics can withstand another round of failure. Faragism waits in the wings for it. There are always things to learn from the past, but if truth be told, New Labour was never new enough, nor Labour enough. In the changed context of now, there is a space for a project that is genuinely both of those things.

More from LabourList

SPONSORED: ‘Industrial hemp and the challenge of turning Labour’s priorities into practice’

‘A day is a long time in politics, so we need ‘action this day’’

Strong support for child social media ban among Labour members, poll reveals