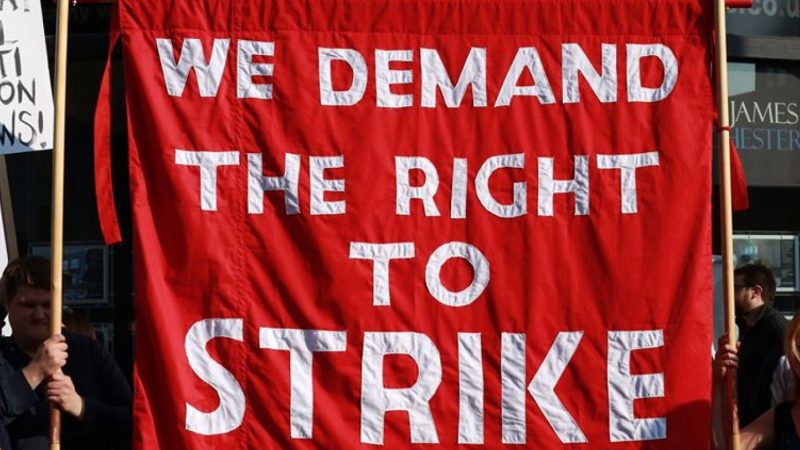

Conflict at work is inevitable, and government should know better than to suggest otherwise. If the Conservatives genuinely want to reduce strike action as they suggest, with their minimum services bill in parliament this week, then they should start by listening to the workers behind them.

British labour history is jam-packed with accounts of workers’ discontent and strikes are once again in the news. With each new strike comes the same narrative that overlooks the inherent power imbalance at the heart of our employment system, creating an alternative reality in which strikers are the problem. It was against this backdrop that Working Voices embarked on a journey to interview workers about their personal experiences of striking.

Working Voices, a series of short films I’ve been working on about workers’ experiences, met with strikers on picket-lines, each explaining how they squared the decision to strike with the significant risks involved, having reached a tipping point that left them with no choice. If the government wants to reduce workplace conflict, it ought to tackle the country’s poor record on investment, work-based training and endemic low pay that have no place in 21st century Britain.

Our interviews revealed the complexities of workplace discontent, which are easy to ignore but much harder to resolve. Pay is important, but workplace grievances are complex and the decision to strike is based on a combination of issues, of which pay might be just one. News headlines cite pay as the cause of striking, but it was never the main reason among those we interviewed. Health workers complained that a lack of investment prevented them from providing a proper level of care.

Workers’ passion for their work can make them strike

In Peterborough a union representative from a multinational explained how his colleagues felt undervalued being offered just two pence above the national minimum wage. In Leicester, as passing cars tooted support, a paramedic of 34 years described keeping a patient alive while sitting with them for hours in an ambulance. Another said he rarely has the energy to go out socially, spending “days off work recuperating and getting over the last few shifts”. And yet, at the forefront of their minds, as they stood in the rain, was the feeling of guilt.

Strike action is often portrayed as a form of anti-social behaviour of a group of difficult and greedy workers. Our interviews with striking workers showed them to be anything but greedy or troublemakers. On the contrary, their passion for their work and occupation is a key factor in their decision to strike.

On a dull day in March, our interview with a paramedic in Nottingham was interrupted by the high pitch siren of an ambulance responding to an emergency call. The truth is that unions already agree derogations with employers, exempting specific workers from participating in strike action. A striking specialist nurse clinician wanted to know how she was to ensure a minimum service level in the event of a strike when there are rarely enough staff on her shift to provide a minimum level of cover on a normal workday.

A young paramedic explained how the pressure has increased: hospitals not being able to discharge patients and how she and her colleagues spent a large portion of time providing services previously provided by GPs.

Like the factory worker from Peterborough, staff in Amazon’s Coventry warehouse worked side by side throughout the pandemic, contributing to billions in profits only to be offered hourly wage increases that still left them just eight pence above the minimum wage. Scratching beneath the surface of working life for this group of workers uncovered stories of exploitation, punitive management and poor health and safety that are redolent of a time long gone. It was shocking to hear stories of how an overtly anti-union management punishes workers for simply talking about trade unions at work.

Portraying strikers as selfish is not lazy journalism – it’s a playbook to preserve power

It would be easy to mistake press reports portraying strikers as selfish and reckless for lazy journalism. But the use of this narrative is far from lazy and is drawn from a centuries-old playbook for preserving power, wealth and privilege that deliberately overlooks the root causes of workplace conflict. It is part of a standardised narrative peddled by our government and by some parts of the media to provide political cover for introducing further restrictions on workplace democracy and, ultimately, as a safeguard against dissent and worker resistance.

The government may shrug its shoulders, but it has an important role to play in the governance of employment relations. The state has a unique ability to shape and organise our working lives, as well as a responsibility, as an employer of millions. One can only conclude that this alternative reality is a deliberate strategy to avoid dealing with the complexities of workplace discontent, such as a lack of investment, low levels of vocational training or development, a lack of career progression and the constant intensification of work. Workers in this country face some of the toughest strike laws and yet are compelled to take strike action out of a profound frustration with a management unwilling to listen. Introducing new a law will not stop them.

More from LabourList

‘SEND reforms are a crucial test of the opportunity mission’

Delivering in Government: your weekly round up of good news Labour stories

Labour place third in Gorton and Denton by-election as Greens gain seat