Imagine that you have just become Prime Minister. It’s your first day on the job. You have managed to scrape a narrow majority and are the first Labour Prime Minister in 13 years.

You’ve run a long campaign based on your shadow cabinet’s formidable economic competence, and you’ve come to power with an ambitious “National Plan” to grow Britain’s economy. The message that carried you to victory was renewal of the United Kingdom and transformation through technology.

And yet, on your first evening in 10 Downing Street, a message comes through from next door. The economy has not been performing well for some time, but the latest economic data is not good. A deficit that was expected to be less severe has materialised far bigger and is impossible to ignore. What do you do?

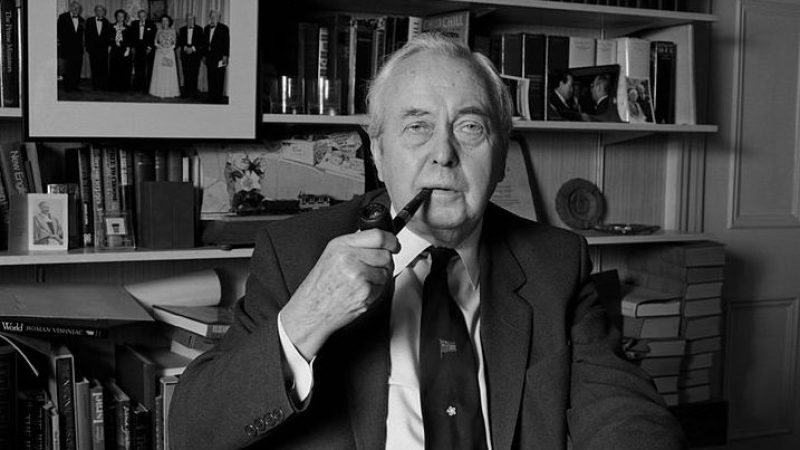

This isn’t a hypothetical story about Keir Starmer’s first days in power. This is the actual story of what happened to Harold Wilson when he won the 1964 general election 59 years ago.

1964 offers more lessons for today than 1997

Too long is spent comparing the next general election to Tony Blair’s victory in 1997. In an unstable global economic climate, there are more lessons to be learnt today from Wilson and the mid-1960s. The dilemma that Wilson found himself in in the first week of his prime ministership shaped his entire term and offers a cautionary tale.

Wilson’s choice on discovering that the UK’s currency was at risk because of a damaging trade deficit was to either suffer the humiliation of being the PM who devalued the pound or struggle on without a devaluation, imposing deflation and budget cuts. Wilson chose the latter option. He placed enormous importance on his personal economic credibility, and he chose to try and save face and soldier on.

The first victim of this decision was his National Plan for economic growth. Wilson had pledged to hit about 4% GDP growth every year of the parliament and had given the job of overseeing this plan to George Brown in the Department for Economic Affairs. An ambitious growth plan was in direct conflict with the economy-cooling policies needed to protect the pound. Brown maintained the charade of delivering on the National Plan for several years, but in truth, it was doomed from the very beginning.

We no longer have fixed exchange rates that make an economic crisis like this possible, but there are reasons Starmer and Rachel Reeves should learn from Wilson’s dilemma.

The winner of the 2024 election will inherit a dire economy

The economic inheritance from this government will be dire – the only question is whether the economy will be smouldering or in flames. Whilst we’ve narrowly avoided a technical post-pandemic recession, growth forecasts are poor. We will look back on the last 13 years as a period of extremely poor economic management.

As Liz Truss learnt the hard way, there are many hidden structural weaknesses and tipping points in the British economy. Whilst Sunak’s plans for re-election require some improvement in headline economic figures, his recent announcements on net zero and HS2 show he has little incentive to tackle long-term challenges, and the longer Labour maintains steady polling leads, the smaller those incentives will become.

Crises are now the norm

Even if Starmer were to avoid an economic crisis on his first day, you’d have to be brave to bet he won’t face one during his first term. We are living in a period of multiple, overlapping crises.

Our planet is in a climate emergency and abnormal weather is already contributing to our economic challenges. A drought in Taiwan recently caused the shut-down of thirsty semiconductor factories, leading to a shortage of chips, particularly those for new cars, in turn leading to a vehicle shortage, pushing up the prices around the world and inflation in countries including the UK. The Russian invasion of Ukraine and instability in the Middle East will both continue to contribute to instability in global energy prices.

So, if we could speak to Harold, what would he tell us? What are the lessons we can learn from that period of 1964 to 1967?

Lesson 1 – Don’t bind your hands too tightly

Firstly, if you bind your policy programme too tightly to (macro)economic factors outside your control, you run the risk of having to junk your programme for government as soon as you hit a bump in the road. One of the reasons the Conservatives have failed to deliver growth policies has been their near-constant chop and change. Labour has made much of their offer to businesses of stability and predictability, but chipping away at the ambition of the green prosperity plan faced with rising interest rates gives little indication of solidity.

As Colm Murphy recently wrote in Renewal: “Labour’s frontbench must assess the resilience of their emerging [Modern Supply Side] policy agenda. They might want to plan through their economic responses to various potential crises.”

A good place to start would be with a Labour government’s fiscal rules. Ahead of an election, there are undoubtedly good electoral reasons for using these rules to communicate something about how a Labour government would approach public finances in power. This isn’t to argue against that.

But it’s essential to acknowledge that if you set hard-and-fast fiscal rules to send signals to the electorate which are tighter than markets call for, you are baking vulnerability to an unstable economy into your programme. These rules should also acknowledge what bond traders already know – borrowing to invest in the productive capacity of the economy is not the same as borrowing to scrap the top rate of tax.

It’s not an over-exaggeration to say that the viability of Starmer and Reeves’ programme of renewal and “securonomics” rests squarely on delivering it because of and despite the unstable economic climate. The Financial Times has referred to plans for falling public investment as a proportion of the economy as a “fresh austerity on public services”. Yet this is what’s implied by a combining the Conservative’s entirely unrealistic post-2024 spending plans with over-tight fiscal rules and a lack of revenue raisers.

Lesson 2 – Don’t put off the inevitable. Act early

The second crucial lesson to learn from Wilson’s gamble? Ultimately, it didn’t work. Wilson put off devaluation to protect his economic credibility, but it was only a stay of execution. The economy didn’t recover, and by 1967, his hand was forced. Backed into a corner, the government devalued the pound, and as predicted, Wilson’s premiership took a severe hit.

It is all easier in hindsight, of course, but it seems clear looking back that if he had taken the difficult choice on day one rather than putting off the inevitable for a few years, the political and personal cost would have been less. Wilson faced a choice between saving the National Plan and saving his economic credibility, and he chose the latter, but because devaluation was ultimately inevitable, he got neither.

Put it another way – if you find yourself in government and you realise that you have bound yourself too tightly to an unstable macroeconomy, the best time to change your mind was yesterday. But the second best moment is today.

Political decisions are hard to unpick but, in retrospect, Wilson probably did have the political headroom in the early days of his administration to devalue the pound. As political cover for changing his position he could have (justifiably) cited the worse-than-expected economic inheritance: “I’ve got into Downing Street and looked at the books and it is far, far worse than I ever expected.”

He could have cashed in some of the good will and positive sentiment an incoming government is gifted, rather than looking for political capital when it is at its nadir. He put off the difficult choice for a worse day, and he condemned his transformational economic programme meaning he saw the upside of neither.

Wilson was certainly constrained by a small electoral majority, something Starmer cannot discount either. But if Starmer were to find himself with a majority bigger than Wilson’s four seats, he will have even more space for manoeuvre.

If the 2024 election delivers a government led by Starmer and Reeves, they won’t have a choice about whether they get to govern without crises. That will be out of their control. But a Labour government can choose how to govern in an age of instability, and the lesson to learn from the past is not to bind your hands too tightly.

More from LabourList

‘Farage lost and blamed Muslims. The data doesn’t support his suspicion’

‘Is the Co-operative Party the key to recovering Labour’s lost young voters?’

Scottish Labour candidates say voters are ready for change – and that the polls may be wrong