This is a story about public capital investment. I know it might not sound like the makings of a thriller, but don’t close the tab just yet. Because this is the story of how Conservative austerity has shredded the fabric of our public realm. How Rishi Sunak tried (and failed) to patch it up. And now – in a final twist – how he’s turned it into a trap for Labour ahead of the 2024 election.

Public investment is the money that the government – local and national – spends on things. It includes infrastructure like roads and railways and the physical parts of public services like school and hospital buildings, as well as less tangible things like research and development. It is no coincidence that it’s these very same things that appear to be crumbling – literally, in many cases.

The Conservatives’ austerity plans after 2010 were based on the idea of cutting public spending, and often departments found it easier to cut investment in tomorrow than services today. This is, of course, the opposite of fixing the roof while the sun’s shining.

The Tories are planning cuts – coincidentally post-election

What’s less well known are the future cuts that Rishi Sunak and Jeremy Hunt have planned. Coincidentally, most of these cuts are due to kick in after 2024.

In what the Financial Times has called “fresh austerity on public services” departmental budgets will be frozen in cash terms from 2024 until 2028, which translates into harsh real terms cuts. Because it’s easier to cancel a hospital that doesn’t exist yet than sack a nurse who does, most of these cuts will manifest in even lower public investment in the future.

Let’s be honest. There is simply no space for these planned budget cuts.

Anyone who has tried to book a GP appointment or catch a train on the West Coast Mainline knows that things currently aren’t working. Anyone who expects the police to investigate stolen bicycles or for children to be safe from falling masonry at school can tell you something has gone wrong in our funding model.

Kick the tyres on any aspect of Britain’s public realm and you’ll probably find something that could do with a bit of investment.

And to put it quite simply: no one really believes that these cuts are even feasible. As Sam Freedman has written: “That little drop in [public spending] between 2025 and 2028 is never going to happen, even though all the parties are pretending it will until the election is over.”

Government spending plans are a fiction

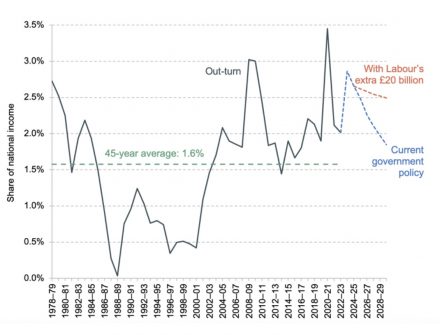

The Institute for Fiscal Studies’ Ben Zaranko ran the numbers recently and his calculations of the government’s public investment plans show a precipitous fall after 2024.

But – I hear you say – Labour intends to invest a hefty £28bn-per-year through its ‘Green Prosperity Plan’. That’s right, but according to Zaranko’s assumptions, the government’s planned cuts are so severe that even with that investment added onto this baseline, public investment is still forecast to fall.

For the benefit of those readers who have been living under a piece of reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete, the public realm in the UK is falling to pieces and there is no fat left to trim. These government spending plans are a fiction.

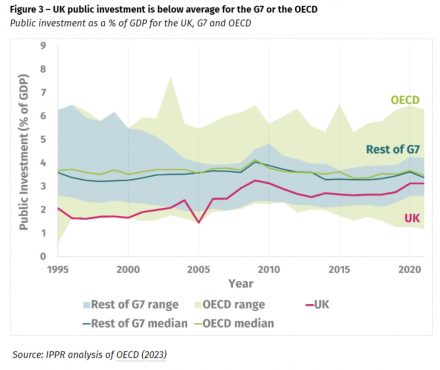

This is all before we get to comparing the UK to other countries. At IPPR we recently showed that since 1995 UK public investment has never even reached the average level of other G7 countries or the OECD club of developed economies. The Resolution Foundation recently wrote about how the UK’s low level of public investment, and its volatility, harms our economy.

They state that the UK investment averages around 2.5 per cent of GDP when economists tell us it should be closer to 4.5 per cent and we chop and change our plans so much that they become less effective.

Perhaps even more damning, when government does invest, it pays way over the odds. Looking just at transport infrastructure data, the UK pays an average of $790 million to build a kilometre of railway line compared to the international average of $212 million per km.

Sunak is reaping what his predecessors sowed

On the part of the government, it’s not really clear what David Cameron and George Osbourne thought was going to happen when they decided to stop investing money in the future of our nation, but Rishi Sunak is now finding out. It might be tragic to watch him reaping what his predecessors sowed were it not that his own fiscal plans are for more of the same.

Turning to Labour, they are most likely to run an election campaign that says something along the lines of “The Conservatives have been in power for 13 years and no one can point at anything that bloody works”.

Yet they have little incentive to draw attention to the government’s trap and if they were to win the coming election are still forecast to cut investment further. They will be stuck between the rock of their fiscal rules and a hard place of further cuts to public investment.

Government budgets only add up on paper

How have we ended up with everyone in Westminster acting as though this makes any sense?

Quite simply there are two ways a budget can “add up”. On one hand, it can mathematically balance. On the other, one can look at whether the plans actually make sense. Westminster’s bean-counters spend too much time doing the former and not the latter. I could set myself a monthly budget where I pretend I’m not going to go to the pub after work or buy lunch from Pret any more. It might literally add up, but it wouldn’t bear any semblance to reality.

An alternative analogy is a homeowner watching water drip through their ceiling who firmly plans their accounts as though there aren’t enormous repair costs looming in the near future. The sums might add up on paper, but they’re going to end up spending the money to fix it whether it’s in their spreadsheet or not.

This is uncomfortably close to what Sunak actually did. We now know from the DfE’s former permanent secretary that Sunak as chancellor reduced the number of schools that would receive repairs to their rooves despite presenting a “critical risk to life” of schoolchildren. When the repairs became so urgent schools had to be closed, the government then stumped up, promised to “spend what it takes”.

This budgetary wheeze likely ends up costing more in the long run (it is presumably more expensive to fix a collapsed roof than to make early repairs).

But it also allows the government to shift realistic estimates of much-needed investment off their books and into a murky space where everyone knows the money needs to be spent but it doesn’t get factored into forecasts. This is exactly what Sunak has done and how he has laid a trap for whoever forms the next government.

More from LabourList

‘Hope starts young: Why Labour must tell the story of a better tomorrow’

LGBT+ Labour suspends AGM amid fears of legal action over trans candidates running for women’s roles

‘Hyperlocal messaging can help Labour win elections: Here’s how’