Labour is used to policymaking processes that build towards three things: the publication of a manifesto, a general election defeat, and a set of recriminations over the extent to which the defeat was the manifesto’s fault.

It is 27 years since a Labour opposition manifesto has turned into the basis of a governing programme. Millions of the people who voted for it then are now dead. Millions of the people Labour is hoping will vote for it now were not even born. 1997’s first-time voters (hello, it’s me!) are now in their late 40s, or older. It’s a long time, is what I’m saying.

Since 2005, then, Labour’s manifestos have all failed. And that has helped Labour’s members and supporters forget that a successful manifesto is not the end of a process, but the beginning of one.

What should a manifesto do?

The purpose of a manifesto is to do at least seven things. It sets out a party’s values, vision and direction of travel. It presents a programme for government, with policies ministers are committed to putting into effect. Its creation shapes and is shaped by a stakeholder management process in which different interest groups are kept happy, or not.

The gradual debate over and rollout of the policies in it, across the course of a parliament, give shape and definition to opposition activity and the project of its leadership. In government, if it is electorally successful, it is an accountability tool to make MPs and peers vote for particular policies.

READ MORE: ‘The five lessons Labour can learn from Claudia Sheinbaum’s victory in Mexico’

At the following election, it is a document by which a government’s success can be measured and on which voters can decide whether to trust them again: did they do the things they said they would do? And finally, it is a campaigning document, attempting to persuade the public: if you want these things, vote for us.

What a manifesto is not is a list of everything a government will do. If Labour wins, it will do things that are not in its manifesto. Every party that has ever won an election has done that. Every party that has ever lost an election has both failed to deliver any of its manifesto promises, and failed to do anything else that its supporters might campaign for.

Labour in government

If the polls are to be believed, Labour will get the chance to deliver on a manifesto, at last. And there is plenty in this one that Labour members and supporters should be excited about, from investment in green transition, to big changes to workers’ rights, to reforming planning laws to build more homes and accelerate growth. Insert your favourite policy here. There may not be any surprises – jump scares are for horror films, not for political parties – but there’s plenty to welcome.

Delivering on Labour’s five missions, as Keir Starmer has repeatedly said, is a decade-long project that will demand focus and commitment across government.

But the difference between a winning project and a losing one is that a winning project can do more things than it has already promised, and be asked to do more things than it has already promised, and face the consequences of not doing more things than it has already promised, instead of just stopping dead on election night.

READ MORE: General election 2024: ‘Why Monmouthshire CLP is setting the standard in this campaign’

I don’t know, for example, whether Labour will scrap the two-child limit for universal credit. But I do know that its political judgement about whether to include it, and its associated spending commitment, in this manifesto is not the same as the political judgements a Labour government will make in its first Budget, or its second, or its third, or the basic attitude of ministers and the instincts of an enlarged PLP, or the influence that effective campaigning can bring to bear on a government as opposed to an opposition.

It makes a difference who the government is, not just because of what it has promised, but because of what it is in politics for.

This manifesto is important because Labour looks likely to win and because these are the tests it has set itself to meet. If it does win, there will be other tests. One of them will be about how successfully everyone who has tried to influence this manifesto can pivot to a challenge they have not had to think about for far too long: how to influence a Labour government.

Find out more through our wider 2024 Labour party manifesto coverage so far:

READ MORE: Labour manifesto launch: Live updates, reaction and analysis

READ MORE: Full manifesto costs breakdown – and how tax and borrowing fund it

READ MORE: The key manifesto policy priorities in brief

READ MORE: Labour vows to protect green belt despite housebuilding drive

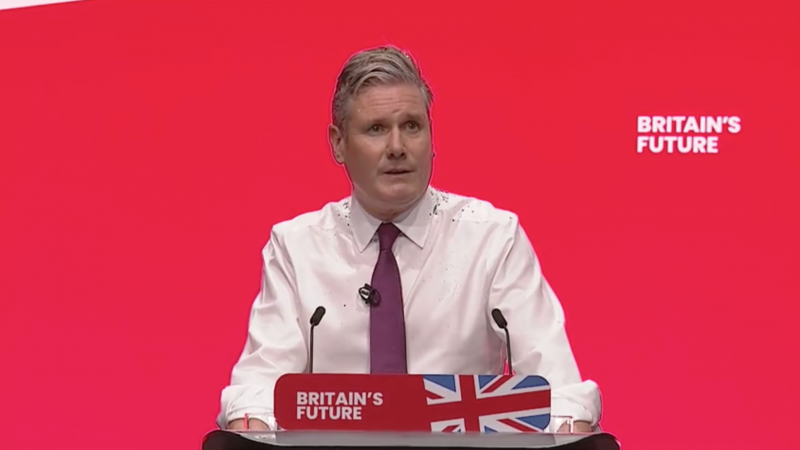

READ MORE: Watch as Starmer heckled by protestor inside with ‘youth deserve better’ banner

READ MORE: GMB calls manifesto ‘vision of hope’ but Unite says ‘not enough’

READ MORE: Manifesto commits to Brexit and being ‘confident’ outside EU

READ MORE: Labour to legislate on New Deal for Working People within 100 days – key policies breakdown

READ MORE: Labour to give 16-year-olds right to vote

READ MORE: Starmer says ‘manifesto for wealth creation’ will kickstart growth

READ MORE: Dodds: ‘Our manifesto is a fully funded vision, while Tories offer a Christmas tree of gimmicks’

Read more of our 2024 general election coverage here.

If you have anything to share that we should be looking into or publishing about this or any other topic involving Labour or about the election, on record or strictly anonymously, contact us at [email protected].

Sign up to LabourList’s morning email for a briefing everything Labour, every weekday morning.

If you can help sustain our work too through a monthly donation, become one of our supporters here.

And if you or your organisation might be interested in partnering with us on sponsored events or content, email [email protected].

More from LabourList

‘What Batley and Spen taught me about standing up to divisive politics’

‘Security in the 21st century means more than just defence’

‘Better the devil you know’: what Gorton and Denton voters say about by-election