The polls are open and the campaign is over. And while the political parties will spend the day getting their vote out, there is very little for the leaders to do now but sit and wait for the verdict.

Yet with power tantalisingly close for Keir Starmer, history shows us that it will be a nervy night for the Labour leader. Here is how some of the leaders since 1945 have spent the day.

Attlee’s quick dash to the Palace

For Clement Attlee, the wait was much longer than 24 hours. Back in 1945, on a wet and miserable July morning, the people of Britain waited patiently for the results of the first general election in a decade. Three weeks earlier they had voted and watched as the ballot boxes were locked up and then stored away in town hall basements (while the votes of servicemen were shipped back from across the globe).

The counting finally began at 9 am. Few expected Winston Churchill, basking in the glow of war victory, to be defeated. Bookmakers offered 5/1 on a Labour victory, with few interested takers.

The first shock came at 10 am when Manchester Exchange, a Tory powerbase for decades, turned red. By midday, as the Conservative Blue Wall in Lancashire and the South crumbled, it was clear that a new political landscape had been forged.

READ MORE: Reeves interview: ‘I’ve campaigned in seats with Tory majorities close to 20,000’

With Labour on course to govern with a majority for the first time in the party’s history, a diner at the Savoy Hotel famously remarked: “This is terrible. They’ve elected a Labour Government. The country will never stand for that.”

But amid the scenes of jubilation, there was a secret plan to prevent Attlee from ever entering Downing Street. He had been an unpopular figure with some in the party during the war for his lack of charisma and inability to inspire large crowds. Two days before the votes were counted, Labour’s “fixer”, Herbert Morrison, sent him a letter stating that several of his colleagues wanted him to stand as leader.

Sensing an opportunity, he wrote that he would accept a nomination. “I am animated solely by considerations for interest in the party and regard for their democratic rights”. But there was no opportunity to put it to the test. Ernest Bevin got wind of the pan and advised: “You get down to the Palace quick, Clem.” Attlee informed the King that he had won the election. “I Know” replied the King. “I heard it on the six o’clock news”.

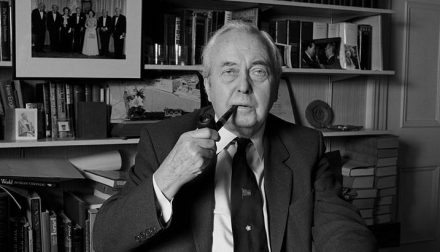

Harold Wilson’s knife edge

Almost twenty years later, Harold Wilson led Labour into an election where they were favourites to win – and there were no plans to replace him as leader. Always calculating what might happen in a campaign, Wilson’s primary concern about election day was whether he could get working-class voters out.

Polling back then ended at 9pm, and he worried that “a lot of our people – my people, working in Liverpool, long journey out, perhaps then a high tea and so on, it was getting late, especially if they wanted to have a pint first”.

When Wilson learned that the BBC planned to broadcast an episode of Steptoe and Son on the night of the 1964 general election, he sensed disaster. He feared that working-class voters would stay at home to watch the comedy, which often drew audiences of 26 million. He visited the home of BBC Director General, Sir Hugh Greene, who agreed to pull the show from the schedule.

Yet it was still a nervous night for Wilson. On the train from Liverpool, he worried that he would have no majority at all. It was only on Friday afternoon that his party reached 316.

READ MORE: ‘New age of hope and opportunity’: Keir Starmer’s last pitch as voters head to the polls

Labour overturned 13 years of Conservative government by winning a majority of 4 —the smallest majority since 1847.

Wilson would win again in 1966 before losing office in 1970. By 1974, many people thought he was yesterday’s man. Edward Heath was expected to win the snap February 1974 election and defeat the miners. Wilson was planning for defeat, too, by creating plans to avoid the press.

After the count at Huyton, he was going to tell journalists he was going back to the Adelphi hotel – but instead, he would go to the Golden Eagle in Kirby, where no one would find him. He then planned to get a plane to London, which would be diverted mid-flight to get him to his country house in Buckinghamshire. As Bernard Donoughue noted in his diary, Wilson was preparing his “getaway plans”. But in the end, he was back on Downing Street as a minority leader.

On the front Foot

Five years later, Labour was expected to lose the 1979 general election, having been behind in the polls for much of the campaign. But Jim Callaghan was more popular than Mrs Thatcher, and doubts remained over whether the public would ever elect a woman Prime Minister. When the polls closed, the BBC reported that the Labour camp was confident of a shock victory. But it quickly dissipated.

On the night, Callaghan travelled down from Cardiff around 5 am before finally catching some sleep at 7 am. He then did a final tour of Number 10 before ending his time as PM by sharing a Cottage Pie with the staff.

READ MORE: East Thanet: Inside the battle for coastal ex-UKIP stronghold not won since 2005

The defeat triggered a lengthy period of opposition, with many disappointing election nights for party activists as the Conservatives dominated. By 1983, few people expected Michael Foot to become Prime Minister, and the main battle for Labour was to prevent the newly formed SDP from becoming the main opposition party. Foot conceded defeat at 2:15 am after the scale of the Conservative victory had become more apparent.

But he immediately turned to journalists at the count and said that “the fight to win the next election starts immediately”. He dubbed the SDP a “bunch of opportunists” as he jumped in a car and headed back to Labour’s Walworth Road HQ. “The few party workers still in the building had been surprised by his decision to turn up at 5:30 am”, reported the Guardian. “The place had been filled with gloom ever since ITN announced its exit poll”.

Neil Kinnock’s gloom

The party was much more confident in 1987. Under Neil Kinnock, commentators believed the party had won the campaign with its new approach to marketing and advertising. Some exit polls showed that a Hung Parliament was possible on polling day. But the hopes proved unfounded as Labour failed in the key marginals. By 12:30 am, the game was up. Kinnock could only point out that the country had made a terrible mistake.

“What we have witnessed is the opening of an even greater abyss and division in the country”. Kinnock arrived at Walworth Road stunned by the result and told exhausted staff that they would win next time. “We are finally talking sense, though voters have long memories and remain wary”.

READ MORE: Sign up to our must-read daily briefing email on all things Labour

By the time of the 1992 election, many people assumed that it would be Labour’s time. Having been ahead in the polls, and the bookmakers favourite to be the biggest party throughout, the exit poll suggested that it was too tight to call. On a bright spring day, Kinnock had quipped that “the sun is out and so are the Tories.

But at Walworth Road, journalists reported that party workers were gloomy. Accredited journalists were “herded together in an upstairs room and offered cans of lager” to see them through the night. Gordon Brown went on television and argued that the Conservatives had lost the right to govern based on the exit poll, but the atmosphere in the Labour camp was rocked by the early constituency results, which showed a national swing to Labour of just 3%. “That’s it” Kinnock told his family, “I’ve just wasted eight years of my life”.

Institutional caution under Tony Blair

On election night in 1992, Tony Blair stuck his hand up to do the broadcast round on BBC and ITV, where he tried to spin the defeat as a good performance for Labour. By the time of the 1997 election, Blair was the clear favourite to win but institutional caution meant that the party could not talk about victory. The day before the poll, strategists had complained about a poll that showed a landslide was imminent – for fear that people wouldn’t turn up to vote.

On election night in 1992, Tony Blair stuck his hand up to do the broadcast round on BBC and ITV, where he tried to spin the defeat as a good performance for Labour. By the time of the 1997 election, Blair was the clear favourite to win but institutional caution meant that the party could not talk about victory. The day before the poll, strategists had complained about a poll that showed a landslide was imminent – for fear that people wouldn’t turn up to vote.

On polling day, Blair was holed up in Myrobella, his large constituency home outside Sedgefield, but was worried when he saw party supporters on television looking too jubilant. Even as it became clear that something historic was happening, party aides worried about how to handle it. Blair has since remarked that he was concerned that the Conservatives would not even put an opposition up by the night’s end.

READ MORE: Small boats and Tory mutineers: Can veteran Mike Tapp win Dover and Deal?

As dawn broke on a new era, Blair was due to open a speech at the Royal Festival Hall with the line: “A new dawn has broken.” But there was a last-minute scramble about what he would say if the weather was grim. Yet just as they arrived, the sun came out and Blair could deliver the line that has gone down in the party’s history.

Labour won 419 seats – the largest the party has ever taken. The Conservatives were down to just 165, their worst performance since 1906.

Labour have not won an election from opposition since May 1997. Many people assume the result is a foregone conclusion tonight. But as the history of election night shows, it will be a nervy affair for Keir Starmer as the results roll in and he thinks about his first words to the nation, as Prime Minister, could be.

Read more of our 2024 general election coverage:

North East Somerset and Hanham: Can Labour mayor Dan Norris consign Jacob Rees-Mogg to history?

Finchley and Golders Green: Can Labour win back Britain’s most Jewish seat?

Small boats and Tory mutineers: Can veteran Mike Tapp win Dover and Deal?

East Thanet: Inside the battle for coastal ex-UKIP stronghold not won since 2005

Sheffield Hallam: ‘Can Labour’s Olivia Blake hold on in Nick Clegg’s old seat?’

Battle of the bar charts in Wimbledon: Inside a rare election three-horse race

Could Labour take ‘non-battleground’ Tory seats across the South West?

Meet NHS doctor Zubir Ahmed, fighting one of Scotland’s tightest marginals

Brighton Pavilion: As Starmer visits, can Labour win the Greens’ one seat?

Labour wants a new generation of new towns. Can it win in Milton Keynes?

Meet Gordon McKee, the 29-year-old son of a welder vying for Glasgow South

Revealed: The battlegrounds attracting most activists as 17,000 sign up

SHARE: If you have anything to share that we should be looking into or publishing about this story – or any other topic involving Labour or the election – contact us (strictly anonymously if you wish) at [email protected].

SUBSCRIBE: Sign up to LabourList’s morning email here for the best briefing on everything Labour, every weekday morning.

DONATE: If you value our work, please donate to become one of our supporters here and help sustain and expand our coverage.

PARTNER: If you or your organisation might be interested in partnering with us on sponsored events or content, email [email protected].

More from LabourList

Government abandons plans to delay 30 local elections in England

‘The cost of living crisis is still Britain’s defining political challenge’

‘Nurses are finally getting the recognition they deserve’