Some call the Fair Pay Agreement ‘Labour’s most radical policy no-one knows about’.

For the first time ever, four unions will negotiate on behalf of a workforce as big as the NHS in one of Britain’s worst-paid sectors – adult social care.

But the government faces growing warnings it risks falling short of expectations, forcing service cuts or fee hikes, or getting axed post-election – unless Labour injects more cash and accelerates the rollout.

What is the fair pay agreement?

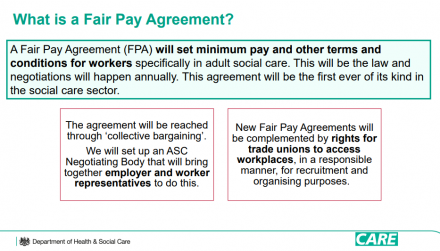

The FPA will oblige employer representatives and four unions to negotiate pay and certain terms and conditions annually for all adult social care workers. Three negotiating bodies will be launched for England, Scotland and Wales.

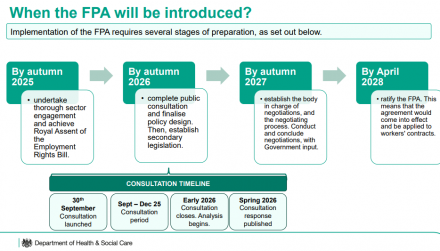

Any deals struck will, unusually, be legally binding on all employers, intended to stop them undercutting each other. Workers should reap rewards from 2028.

Why is the FPA needed?

Around one in five residential care workers lives in poverty, according to Health Foundation fellow Lucinda Allen.

Chronic poor pay reflects “systemic problems”, from insufficient funding to a particularly marginalised, under-unionised workforce. Migrants, women and ethnic minorities are over-represented. Migrants’ bargaining power is especially limited by reliance on employer visas.

Care minister Stephen Kinnock told LabourList care workers faced a real struggle putting “bread on the table”. Even experienced workers often earn little more than new recruits.

“We’ve got the constant challenge that people will say ‘I can get paid more down the road at that supermarket’.”

Turnover is high. A government report recently acknowledged this “increases risks around access to high-quality care”.

International recruitment has helped plug gaps, but government is clamping down – despite over 100,000 vacancies remaining. “Now we start paying an attractive wage – or social care collapses,” one influential Labour policy figure says.

What could the FPA achieve?

Employment expert Melanie Simms calls sectoral collective bargaining “the most effective way of redistributing wages and wealth ever invented”.

Keir Starmer says the FPA means a “higher floor”, with not only fairer pay, but more progression, training and rights.

This should spell greater “professionalisation and respect” – and boost retention and skills, according to Public First director Andrew Harrop.

Fabian analysis argues it could eliminate staff shortages, and cut delays discharging hospital patients. Labour has argued better pay boosts productivity too.

READ MORE: Has Labour watered down plans to boost union rights via sector bargaining?

For Kinnock, it is also an “important part” of Labour’s journey towards a National Care Service.

Harrop, who led a Labour care review while Fabian General Secretary, says more standardised terms can move a fragmented, private service towards being a unified public service – where workers feel like NCS staff whoever their employer, as NHS staff do.

Meanwhile bargaining power could increase at workplace level. One union source called it a “game-changer” for membership recruitment, with hopes of public sector-style unionisation rates.

Is there enough money?

Major hurdles loom, however. The first is cash.

The government promised £500 million for representatives to negotiate over in year one in England. Simms says it will “focus minds”, and incentivise employer engagement.

But she warns it’s not enough – and many employers, unions, councils and experts agree.

Experts note it would only lift wages by 15-20p an hour. Just matching the second-lowest NHS pay band would cost £2.3bn.

“It’s not going to make a huge difference,” says Mel Weatherley, co-chair of the Care Association Alliance, one employer group involved in talks. She suggests there are “unrealistic expectations” over the FPA.

Government has suggested negotiating bodies cannot propose over the £500m envelope. That looks a likely flashpoint. The Local Government Association recently warned proposals may well exceed £500m. As Weatherley notes, many employers and unions “agree the workforce is underpaid”.

Could pay hikes force cutbacks?

Who could find the cash? Even if the department agreed, “I’m absolutely certain they haven’t convinced the Treasury”, one sector source claims. Harrop notes government’s efficiency drive.

As for care providers, a new survey by their main umbrella group suggests most already expect to use reserves and raise private fees to get by. “We’re lucky if we’re making ends meet,” says Weatherley.

The LGA fears providers rejecting contracts or cutting services. Studies suggest they compensated for past living wage hikes by hiring staff at less senior levels or for fewer hours – or through a “significant deterioration in care quality”.

If similarly cash-strapped councils have to pay, Allen has warned they may ration care or likewise cut other services.

Who will represent 18,000 employers?

A second widely perceived challenge is employer, worker and funder buy-in. With quarterly meetings already, Kinnock is proud of how the sector and unions have “co-produced” the proposals, and multiple sources praised consultation to date.

But he admits uniting providers is “challenging”. The government proposes letting an umbrella group of provider associations, the Care Provider Alliance, negotiate opposite unions. But it represents at least 10 smaller membership bodies. Their interests may not be “completely aligned…making agreement difficult”, the Institute for Government has warned.

Many of England’s 18,000 estimated providers reportedly don’t even belong to them.

Weatherley argues government decisions elsewhere are already undermining engagement by angering employers.

Labour recently offered compensation for national insurance hikes and accelerated settlement routes for NHS and other public sector jobs – but not for private and third sector care jobs.

Pay negotiations go far beyond provider associations’ current roles and experience, too.

For unions, it’s bread and butter. They still face challenges speaking for workers, however, given around 80% aren’t unionised.

Meanwhile the LGA argues councils aren’t sufficiently represented, as commissioners and sometimes employers. Individuals funding their own care make similar complaints.

Could employers ignore what’s agreed?

Buy-in matters to not only reach the right deals, but also ensure all parties understand and uphold them.

Weatherley argues it’s vital to ensuring agreements aren’t seen as “another tax” or “imposition”, and suggests smaller employers may not understand arrangements.

Experts note minimum wage underpayment is already rife, and question whether Britain’s new labour rights watchdog has enough cash to avoid past poor enforcement.

“That does call into question whether people will see the benefits,” says Allen. The IfG fears the planned watchdog won’t even be ready, either.

Meanwhile the GMB’s Will Dalton argues the FPA must expand to cover shared lives and other self-employed care workers, to avoid both them missing out on benefits and employers using bogus self-employment to dodge the FPA.

How should money be spent?

A third challenge is what’s actually negotiated on. Government consultation questions do appear to reflect key sticking points. One is whether parties can bargain over areas outside contracts – like training, health and safety, travel reimbursement, bullying, discrimination and family-friendly policies. It’s understood unions want as wide a remit as possible; many employers likely won’t.

Another is what’s prioritised in year-one talks. Pay and sick pay appear likely to be unions’ priorities. One trade-off is between raising minimum pay to tackle poverty and boost entry-level recruitment – which looks most likely – and raising pay for more experienced or qualified staff to boost skills, retention, or specialist recruitment.

READ MORE: ‘Employment Rights Bill must go further to reform disgraceful sick pay system’

The GMB has a “Fight for £15” campaign on minimum pay. But some employers fear eroding pay differentials could be “existentially damaging” for areas struggling most to recruit, like mental health, according to Weatherley.

Kinnock says it’ll be up to negotiators, and Weatherley’s hopeful of reaching agreement.

if disputes on such issues drag on, or employment legislation’s further delayed, some fear the election could come before workers benefit – making repeal by the Tories or Reform far easier.

A Resolution Foundation report this week is expected to echo sector voices warning urgency is vital. Simms, a contributor, notes a new government in New Zealand recently “cut the legs” from similar reforms.

How radical is this?

After decades of declining union power, “this would be a rare example of extending collective bargaining for a large workforce”, as one union source puts it.

Strengthening sectoral bargaining was a key 2017 manifesto commitment.

Last year’s pre-election Plan to Make Work Pay pledged to assess how FPAs might benefit other sectors.

“I haven’t heard anybody saying we wouldn’t be looking at this,” Kinnock said. He hopes personally it will be a “trailblazer”, calling it “the epitome of a Labour policy: pro-worker, pro-business, pro-care, pro-compassion”.

Still, sectoral bargaining is the norm in many countries, including liberal economies like Ireland and Australia. It already occurs in Britain’s public sector. Most British workers were covered by sectoral deals in the 1970s. A quarter, including the most vulnerable, were once covered by mandatory Wages Councils.

Yet Labour in power has said little about other low-paying sectors, and opposition saw pledges diluted. Talk of FPAs “across the economy” has gone. Hence, perhaps, a recent TUC agreement to campaign for more.

Meanwhile 15p more an hour won’t transform lives.

But Simms and others note the minimum wage started modestly. Yet as she told a recent conference, low pay by international standards has now been “regulated out of existence”.

Perhaps care workers can dare to dream.

Subscribe here to our daily newsletter roundup of Labour news, analysis and comment– and follow us on Bluesky, WhatsApp, X and Facebook.

Share your thoughts. Contribute on this story or tell your own by writing to our Editor. The best letters every week will be published on the site. Find out how to get your letter published.

-

- SHARE: If you have anything to share that we should be looking into or publishing about this story – or any other topic involving Labour– contact us (strictly anonymously if you wish) at [email protected].

- SUBSCRIBE: Sign up to LabourList’s morning email here for the best briefing on everything Labour, every weekday morning.

- DONATE: If you value our work, please chip in a few pounds a week and become one of our supporters, helping sustain and expand our coverage.

- PARTNER: If you or your organisation might be interested in partnering with us on sponsored events or projects, email [email protected].

- ADVERTISE: If your organisation would like to advertise or run sponsored pieces on LabourList‘s daily newsletter or website, contact our exclusive ad partners Total Politics at [email protected].

More from LabourList

‘Energy efficiency changes must work for older private renters’

‘Labour’s creative destruction dilemma’

Economic stability for an uncertain world: Spring Statement 2026