Very few expected any of the headlines generated by this week’s Budget to focus on Defence.

But let us be in no doubt of the importance of the UK meeting NATO’s target of spending at least 2% of GDP on Defence. It is the premium on an insurance policy to enhance the nation’s security, and allow Britain the opportunity to play a positive, progressive and internationalist role in shaping global events. But it also stands as an important symbol of the UK’s enduring commitment to NATO, which, in an increasingly uncertain and dangerous world, must remain the cornerstone of the UK’s multilateral security arrangements.

However, just because yesterday’s announcement is to be welcomed, it does not mean that it shouldn’t be properly scrutinised. For months and months Tory Ministers failed to guarantee that they would meet the 2% target, yet within weeks of forming a new Government have been able to do just that. So, how did they do it?

Firstly, the Treasury has agreed to a 1% increase in spending on military equipment, as was promised before the election. And secondly, they have also allowed for further investment in our intelligence agencies. Whilst both of these measures are welcome, they would still leave the UK falling billions short of meeting its 2% target up to 2020.

Indeed, as was reported in the Financial Times yesterday, it appears as though Ministers have crossed the line by allowing the spending on the Single Intelligence Account (from which Mi5, Mi6 and GCHQ derive their funding) to count towards its 2% of GDP target. Parliamentary Questions show that this wasn’t the practice of Tory ministers in the last Parliament, but now, fearful of falling below the 2% threshold, they appear to have changed tack. The public may also question how much £800m of military pensions, now included as part of as ‘Defence spending’, contributes to the UK’s ability to project force too.

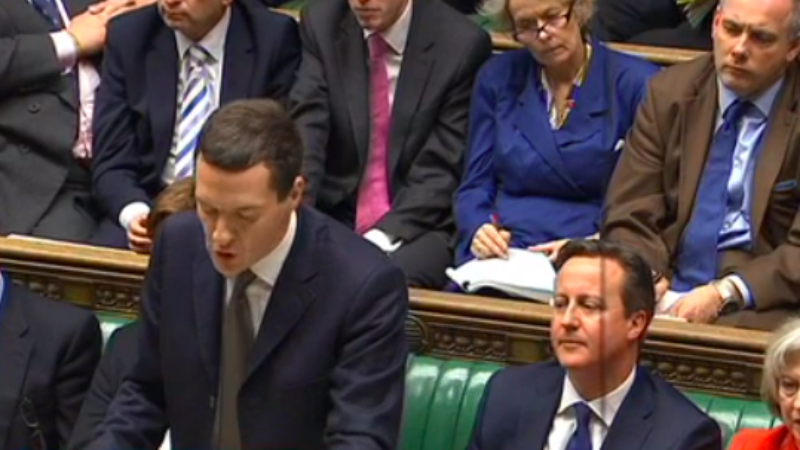

In the light of this the Government would be wise to steer well clear of triumphalism. Wednesday’s announcement does not mean that all of a sudden the MoD is awash with cash; Defence Ministers still have to contend with very tough choices in this Parliament. Indeed, Service Personnel—whose morale has ebbed away on David Cameron’s watch—listened to George Osborne tell them on Wednesday that their pay will continue to be capped to soon fall below inflation, and that many of them are to be further hit by the Chancellor’s changes to tax credits. And, of course, there are still further redundancies to our Armed Forces yet to come in this Parliament. This portion of the MoD budget—which is particularly vulnerable to fluctuations in oil prices and currency rates—appears to have received a flat real terms settlement, meaning difficult decisions still lie ahead.

Furthermore, as the National Audit Office (NAO) made clear earlier this year, even with the 1% annual increase in funding for kit there are serious questions about the affordability of the Equipment Plan. Given the historical problems of cost and time overruns in major Defence procurement projects, the NAO are right to question whether the Government’s contingency fund is sufficient. Any slippages on this would clearly pose a serious threat to the delivery of Future Force 2020 and to the capabilities of our Armed Forces. Also, whilst the Red Book confirms that regular Army numbers are to stay at 82,000, it makes no mention of the other Services or of the Reserves. So Ministers must confirm whether or not they still remain committed to the delivery of Future Force 2020.

It is clear then that the MoD has not become a land of milk and honey overnight. Crucially, their latest announcement does not mean that Defence Secretary or the Prime Minister can avoid facing tough questions over this year’s vital Strategic Defence and Security Review (SDSR).

Put simply, altering Whitehall accounting mechanisms by including Intelligence as part of ‘Defence spending’ does not mean that the country can afford another SDSR like that which we had in 2010. That was a review that was strategic in name only, cutting capabilities without asking the fundamental questions about how to advance UK interests or security. It left the country with an aircraft carrier without any aircraft, and left the UK without any maritime patrol capabilities.

The authors of the next SDSR must face up to a wide range of strategic challenges. The past few years have seen the emergence of a resurgent Russia, the rise of ISIS in the Middle East, and the accelerated growth of cyber terrorism. And, of course, as with every proper Defence review that has come before it, this SDSR will have to contend with the as yet unknown threats that may arise in the future.

To do the multifaceted challenges of this Review justice, Ministers should consult as widely and extensively as possible, speaking to academics, industry, and members of the public. This is something which the previous Labour Government did as an integral part of its Review, which was fundamentally lacking in 2010, and which we have seen little sign of changing this time around.

So it is of course welcome that the UK will continue demonstrating its commitment to NATO throughout the course of this Parliament by meeting the 2% threshold. But it is vital that we bear in mind how it was that Ministers got there, as well as the significant challenges that lie ahead for UK Defence over the next five years.

Kevan Jones MP is the Shadow Armed Forces Minister and Member of Parliament for North Durham.

More from LabourList

‘I was wrong on the doorstep in Gorton and Denton. I, and all of us, need to listen properly’

‘Why solidarity with Ukraine still matters’

‘Ukraine is Europe’s frontier – and Labour must stay resolute in its defence’