Clearly we are living in deflationary times. In 1981 when you wanted to find economists who would criticise government policy 364 of them were on hand to sign a group letter. Last week a repeat performance managed to rustle up only 79 signatories.

It could be that feelings are not running so high these days, or perhaps as a result of cuts to university departments there are just fewer economists about to sign letters. Maybe we live in more fearful times, and some silent critics are too nervous to put their names to such a document.

Either way, the latest attempt to register formal and authoritative disapproval of government policy is unlikely to change anything much, just as the letter from the 364 (a group which included Mervyn King, Amartya Sen and Julian Le Grand) failed to shift Mrs Thatcher and Geoffrey Howe from their chosen course of action. The lesson of both these letters is that facts and political reality are not the same thing.

The 1981 budget, whatever its alleged virtues, did lasting harm to the British economy, accelerating deindustrialisation, sending unemployment soaring, damaging communities and undermining manufacturing capacity on a permanent basis. Today’s worries about an unbalanced UK economy are a direct result of choices made over 30 years ago – although, in fairness, Britain’s manufacturing woes have other, older causes.

The “political reality” of all this is, however, rather different. According to this version of events, the 1981 budget was all part of a painful but necessary process of shock therapy, dragging the UK out of post war decline and creating the conditions for future economic prosperity. That boom led once again to bust by the end of the decade, with inflation and unemployment once more out of control, does not always get a mention in this version of the story.

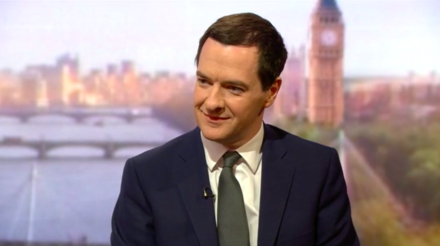

So it is today with the chancellor’s latest move to make budget surpluses permanent in “normal” times. The facts about the modest pre-crisis deficit in 2007/8 are known and understood by economists. But political reality has conflated the international financial crisis with Labour’s “wasteful” spending. People whose family members were treated by an improved NHS or whose children benefited from increased staffing levels in new school buildings know for a fact that Labour “spent too much” in office.

In the election campaign, Labour tried to make its case using facts that only a minority of the electorate was prepared to accept. Political reality proved too powerful, as it usually does. Deborah Mattinson at Britain Thinks often argues that political parties have to “start where people are”. That means accepting and working with political reality, not your own preferred set of facts. Even the most consistent supporters of Ed Miliband’s leadership worried that there was a lack of ruthless pragmatism in the top team, and a reluctance to recognise political reality and respond to it.

Whoever becomes the new Labour leader will not have the luxury of being able to tell voters that their view of the economy is faulty. The new leader will have to deal with political reality, not narrow and unconvincing facts. It is not a question of embracing “post-truth politics”. It is about taking part in conversations where you have a chance of being heard. Nor does this mean accepting the Conservatives’ characterisation of the state of the economy. It does mean attempting to regain credibility by talking convincingly about the world voters inhabit and recognise.

There is a distinctly Labour way of talking about these matters that can still find a large and welcoming audience. The challenge for the new leadership team will be to find it.

As John Gardner, the American politician and thinker, said:

“Our problem is not to find better values but to be faithful to those we profess.”

More from LabourList

‘Is there an ancient right to jury trial?’

‘To tackle the housing crisis, the Treasury must rethink how it values social housing investment’

‘Labour action on extreme poverty can stop voters going Green’