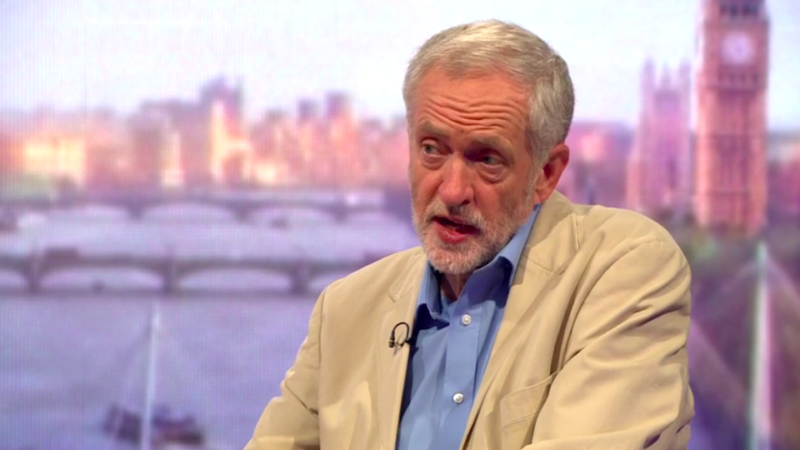

Three months ago, to say that Jeremy Corbyn would win the Labour leadership contest would have been absurd. Two months ago, it would have been brave. For the last month, at least, it has been a statement of the bleedin’ obvious.

Corbyn has confounded all expectations by being successful. Now he must confound the expectations of many in order to be successful.

As I have commented before, the Corbyn campaign was excellent in many respects. They had clarity of message, and delivered it well. But what is popular with Labour supporters and members is not, as we all should know, necessarily popular with the wider public. His ability to excite support outside of normal channels aided his remarkable victory, along with the new £3 supporter system, but Labour will need millions of extra voters, not hundreds of thousands, to stand a chance in 2020.

His victory must be interrogated with the same vigour as an inquest into a general election defeat for Labour. He arrives into his position with the odds stacked against him. The Labour Party is in a dreadful electoral position following a resounding defeat, and his victory has been anticipated by dire warnings from almost every major party figure of the last 30 years.

Labour will need at least 11 million votes to be in with the chance of a majority in 2020. There are not already 11 million people in this country simply waiting to vote for a Corbyn-led Labour. They need to be won. The hard work starts now.

There are elements of his campaign that will not translate well into his new role. Being unpopular with the mainstream media is great for cementing the support he already has, but will harm attempts to branch out and win new support. The same is true of support among the Parliamentary Labour Party. Sitting at odds with them worked during this contest as many in the grassroots felt MPs were out of touch, but this will quickly turn into stories of a divided party – thankfully, he has already made noises about rectifying this. Who he picks for his shadow cabinet will be his first test here.

No longer, too, can he put forward a policy, only to argue that it was only floated as a possibility when it is subject to criticism. As Leader of the Opposition, it is his job to offer an alternative Government, with an agenda ready for scrutiny.

At a pre-rally press gathering last month, Jeremy was asked how he could win over voters who had plumped for the Tories over Labour because they viewed Cameron as more prime ministerial than Ed Miliband. He replied that he did not want people to decide their vote as though we have a presidential system, when we do not. But choosing on what basis voters make their decision is not a luxury afforded to politicians, and his team must understand the real reasons he has won in order to capitalise on the momentum.

For instance: people actually like him.

A favoured explanation of the Corbyn’s popularity is that his campaign has been about policy and not personality – but this is an oversimplification. With an almost identical policy platform, Diane Abbott failed to win in 2010, and failed to win Labour’s London Mayor selection in 2015. Answering why this is will throw up some uncomfortable truths, but even they will not tell the full story. Put it this way: would John McDonnell have won the leadership if he and not Corbyn had run? The answer, unequivocally, is no.

Whether we like it or not, however, people do decide their vote on who they like on a personal level, and Corbyn’s team must recognise that he as the candidate has been a huge boost to their campaign so far. When you have an asset, you should utilise it. Of course, it plays into his appeal to say that he has won purely because of policy and not personality, but it is simply not the case.

Part of what has made Corbyn successful is, of course, the support of large trade unions who did not give their backing to Abbott. He has been a forthcoming friends of countless grassroots campaigns, from austerity to housing to war, and has not been known to turn down an invitation to a picket line, whether cameras are there or not. Over the course of decades, this has created goodwill with broad left activists, who have the contacts and organisational skill to arrange the impressive rallies that have defined his leadership bid.

It also helped that his opponents in this race appeared unelectable. This is a shortcoming that the next Tory leader will not suffer from. This is why ensuring there is a cogent electoral strategy is a must. We cannot pursue a strategy, namely the prioritising non-voters over Tory voters in marginal seats, that research of the Fabians and TUC tells us will fail.

It would make an excellent early intervention as leader if Corbyn were to set out how he seeks to build a broad base of support, and will make special efforts to win over 2015 Conservative supporters. He could spell out how he means to do it, with a string of populist policies that could arguably attract those groups. If he were to do this as a speech at the Trades Union Congress in Brighton this week, all the better.

It would wrongfoot opponents who wish to paint him as not serious, and start his leadership with an unexpected stance that would open up debate about how Labour goes about convincing the voters it needs to win in 2020 – a conversation that has been too often absent from the leadership contest. Jeremy Corbyn has the ability to surprise; he should use it.

More from LabourList

‘Why solidarity with Ukraine still matters’

‘Ukraine is Europe’s frontier – and Labour must stay resolute in its defence’

Vast majority of Labour members back defence spending boost and NATO membership – poll