One evening at Labour Conference 2009, those of us attending from my constituency party met for a meal in a restaurant on the Brighton seafront. Our waiter was very excited to regale us with his familial tie to Labour royalty.

“My great-great uncle was a Labour Prime Minister,” the waiter told us. “But I’m afraid you won’t like him: it was Ramsay MacDonald.” On cue, our well-oiled delegates treated him to panto hisses.

“Now,” interrupted one, “I actually think there’s room for some reappraisal of Ramsay MacDonald.”

If the exchanged glances across the table in that moment didn’t give it away, then the ensuing hour of conversation confirmed that Labour’s first PM is unlikely to be receiving a re-evaluation from the party grassroots anytime soon.

A mere 85 years on from the formation of the National Government, Labour MPs will be well aware how muddied MacDonald’s name remains in the party when they walk past his portrait which hangs outside the venue for the weekly PLP meeting. No matter how rowdy things get these days, its tempting to wonder what could have been heard if you cupped an ear to the door of Committee Room 14 on a Monday night in 1931.

The repercussions of MacDonald’s decision to work with the Conservatives have not only coloured his own legacy, but shaped Labour’s approach to cross-party politics ever since – especially when it comes to the Tories.

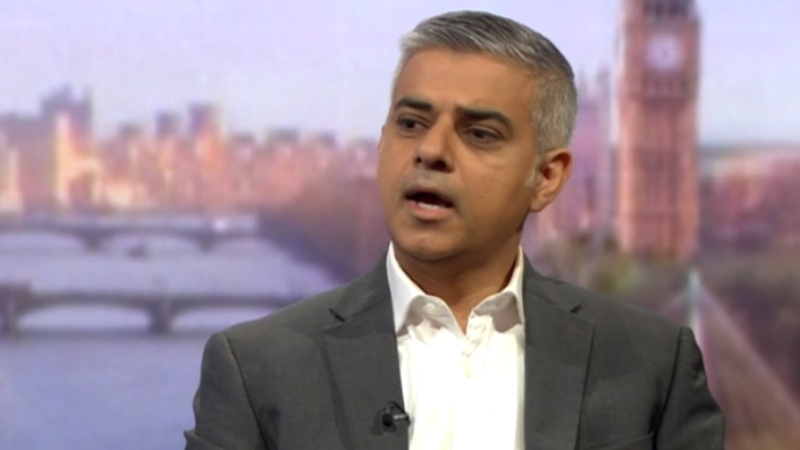

We saw it in the way many have pinned Scottish Labour’s failures on the plurality of the Better Together campaign, and how some reacted to the likes of Alan Milburn and Andrew Adonis taking up advisory roles to the government. And we’ve seen it again with criticisms of Sadiq Khan sharing a platform with David Cameron on the Stronger In campaign this week.

Both Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell have refused to share platforms with the Tories during the EU campaign, believing it to have been a major mistake during the Scottish independence referendum. That’s their call, and it’s a fair one to make, as long as an analysis of the way back for Labour in Scotland doesn’t revert to a belief that the party’s problems began in September 2014 – a glance at the 2011 election results should quickly put that straight.

But neither should others be attacked if they think that the best way to argue for an In vote on June 23 is by showing a cross-party consensus.

Last night, McDonnell reportedly told a Labour In rally that “sharing a platform with them [the Tories] discredits us”.

Actually, Khan’s move is not bad politics. He recognises that not only was he elected as a “unity over division” candidate a month ago but, as Mayor of London, he also needs to represent the one million people who voted Tory in there less than a month ago. By appearing with Cameron he has, on a level, forced the PM to disavow the nasty campaign he endorsed against Sadiq, as well showing he is willing to build relationships across the divide if it is in London’s interest.

Khan, riding high on a wave of popularity after a stonking election victory, is also in a wildly different position to Scottish Labour two years ago, and won’t face the same backlash.

We often hear that people would like politicians to toe the party line less and stand up for what they believe in more – it certainly seems to be a major part of Corbyn’s appeal. As we get closer to the referendum date and the polls start to look increasingly shaky for Remain, Khan has done exactly that. He doesn’t deserve the Ramsay MacDonald treatment.

More from LabourList

‘Someone to bring them together’: The Gorton and Denton by-election campaign from the ground…

Labour ministers, MPs and mayors rally behind PM amid calls for resignation

Scottish Labour leader Anas Sarwar calls on Starmer to resign