Politicians often boast of having fully costed manifestos. Theresa May was rightly lambasted for going to the country without having costed her policies.

Knowing, actually knowing, the price of bread is a staple of politics. Senior politicians make a point of learning the costs of milk, eggs and petrol before any interview. For several months, however, Labour politicians have been walking around the Brexit supermarket, picking items off the shelves without much regard to price.

We are debating leaving the European single market. A large group of MPs from the north and midlands are worried about the requirement to maintain freedom of movement as a member of the single market. They are joined in an uneasy alliance by a small group around the leadership who oppose European Union state aid rules, believing them to make more difficult the provision of nationalisation and aid to strategic industries. This week they have been joined in earnest by an even smaller group who worry about the UK being a “rule taker” in the European Economic Area (EEA) rather than a rule maker. Barry Gardiner, the shadow international trade secretary, has expressed this view most vividly, describing Norway – in the EEA but out of the customs union and the EU – as a “vassal state”.

As Gardiner does, these groups are happy to discuss the political price of staying in the single market. I haven’t yet seen them engage with the economic cost of leaving. So what is the actual price of leaving the single market?

Several reputable economic analyses, from the London School of Economics, the Treasury and NIESR have estimated the cost of Brexit. They each find the same hierarchy of effects: the further Britain travels from the single market, the greater the economic loss.

Moving briefly into the world of jargon, the economic pain can be divided into two types. First, there are the so-called “static” effects whereby fewer exports, a higher exchange rate, and lower foreign direct investment depress economic growth. These may accumulate over time – as leaving the EU means regulatory standards gradually diverge and make it harder for the exporters of vacuum cleaners, Welsh lamb or insurance products to sell in the European market. Second, over time trade also improves productivity – the amount we produce per hour – think of Nissan bringing in new working techniques, or Dyson innovating in response to foreign competitors. So-called “dynamic” effects also accumulate over time: so less trade leads to lower productivity and lower living standards.

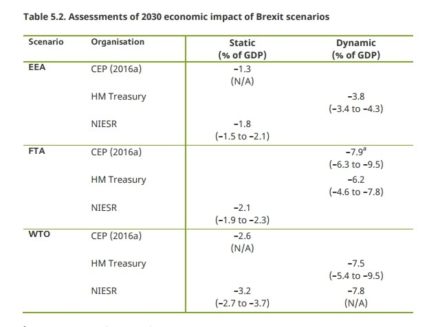

These effects are summarised in the Institute for Fiscal Studies table below. They compare the soft Brexit of the EEA with the hard Brexit of a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) such as Switzerland’s or the EU-Canada deal, and the “stupid Brexit” of falling back onto World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules.

What does a reduction in GDP mean in real life? One way to calculate GDP is to add up everyone’s wages, business profits, and rents. Put simply, leaving the single market means fewer jobs and lower wages. As the TUC general secretary Frances O’Grady said: “If we leave the single market, working people will end up paying the price. It’d be bad for jobs, for work rights and for our living standards.”

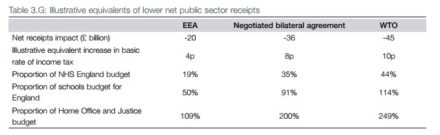

And what does leaving the single market mean for public services? Well the Treasury analysis provides one answer. Even staying in the EEA – the least bad form of Brexit – is equivalent to an annual tax loss of £20bn a year by 2030. This is a huge sum – greater than the Tories’ £12bn annual welfare cuts which are currently causing such misery. A “stupid Brexit”, where we rely on WTO rules, implies a further £25bn loss on top of the £20bn loss – a total of £45bn each year.

But let’s assume we get lucky and a future Labour government is able to negotiate a free trade agreement closest to what some in the Labour party currently aim for: tariff-free trade access to the European market. The Treasury analysis suggests that this is equivalent to a further £16bn in lost tax revenue (a total of £36bn annually). Such staggering sums can be difficult to comprehend so comparisons can be useful. That additional £16bn tax loss (on top of £20bn ) is equivalent to:

- Around 16 per cent of the budget for NHS England;

- four pence extra on the basic rate of income tax;

- Around 41 per cent of England’s school budget.

As a reminder, this would come after years of austerity, and during a period in which the NHS has said it will need an extra £30bn a year by 2020 to cope with an ageing population.

The debate within the labour movement about leaving the single market has focused on three issues: freedom of movement; state aid and nationalisation; and becoming a ““rule-taker”. It should also focus on a fourth – the £16bn cost of leaving. Next time you hear someone say “access to” the single market, rather than “member of”, remind them that there is a £16bn difference in price. Why spend years campaigning against austerity while arguing for a type of Brexit that will extend its icy grip?

Nick Donovan is organising a loose network of Labour members to change party policy to remain a member of the European single market, including by introducing a CLP motion.

More from LabourList

Which ministers have done the most and fewest broadcast rounds in year one?

‘Welfare reforms still mean a climate of fear. Changes are too little, too late’

Welfare bill: Which MPs are still voting against reforms?