The Labour Party’s post-conference broadcast ‘Our Town’ spoke volumes about the party’s electoral strategy. Focussing on the need to deliver social and economic regeneration to non-metropolitan areas, not once mentioning Brexit, it encapsulated the electoral priorities of Jeremy Corbyn’s team.

The Labour leadership clearly believe not only that the most vulnerable element of their electoral coalition are the non-urban constituencies in England and Wales, but also these areas also represent a potential electoral opportunity. Little surprise that the first two stops on John McDonnell’s post-conference country-wide tour were the constituencies of Browtowe and Hastings and Rye, where a majority voted Leave and the Conservatives sit on majorities of under 1,000 votes. The calculation is that opposition to Brexit would negate any attempt to woo voters in places like this.

And it has some merit. That being said, it is also something of an oversimplification. Even if a constituency strongly backed Leave, it does not follow that most Labour voters there did so. YouGov’s Brexit tracker has shown the number of Labour voters who think Brexit is a bad idea has remained consistent at between 67-72%, with the last poll showing that 68% of Labour voters hold this view.

Moreover, it does not even necessarily follow that those swing voters who might hold the key to majorities in those constituencies are Brexit supporters. Analysis by Ian Warren and Kevin Cunningham of the 100 closest-fought constituencies found near-identical numbers of Labour Leavers and Conservative Remainers. And, as Geoffrey Evans and Florian Schaffner set out in this report, Remain has strengthened as a political identity at a faster rate than the Leave identity since 2016.

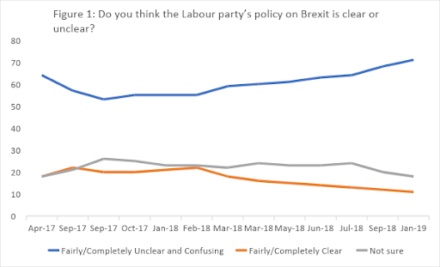

This is the Labour Party’s ongoing Brexit bind: ambiguity might be the best available strategy, but it may not be an effective one when it comes to maintaining Labour’s 2017 electoral coalition. This ambiguity comes at a price. Rather than being all things to all people, the Labour Party’s Brexit position could end up pleasing no one. As Figure 1 shows, a record 71% of voters – 18% higher than following the general election in September 2017 – describe Labour party policy on Brexit as ‘unclear and confusing’.

Remainers demanding a further referendum often argue that this constructive ambiguity is not just undesirable, but unviable. Perhaps the biggest message of Jeremy Corbyn’s surge in the general election of 2017 was that historical precedents can be overturned. No two elections are the same and there would be a certain irony if the Labour leadership, in the expectation that their fudge in 2017 will reap similar reward next time, were blind to the threat.

It is also worth noting the effect of a small but perceptible increase in support for Remain that has become apparent in opinion polling. This shift, mainly driven by demographic churn in the electorate, translates into a potentially significant shift in terms of constituencies. Chris Hanretty’s constituency-level MRP data estimates 403 out of the 632 constituencies in England, Scotland and Wales had majority Leave support in 2016. Now, the situation is reversed: 392 have Remain majorities; 240 would still back Leave. Hastings and Rye was 56% Leave in 2016, but is now 50:50; Broxtowe was 52-48 in support of Leave, but polls suggest it would now be 54-46 Remain.

These constituency-level analyses feed into the fast-evolving internal politics of Labour’s position in the House of Commons. Significantly, Labour MPs have moved away support for a soft Brexit from single market membership. When we polled Labour MPs in December 2017, 8% said single market membership would not represent a Brexit that honoured the referendum. The figure today is 36%.

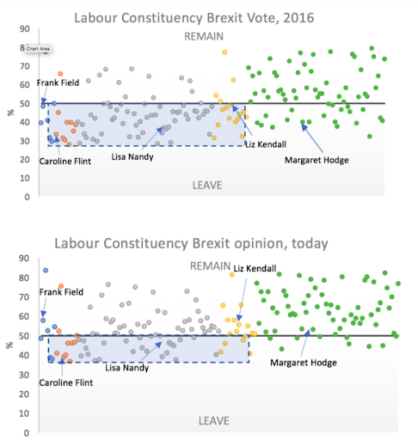

These MPs might be emboldened by the fact that, on the polling evidence, their constituencies have moved towards Remain. Figure 2 maps the Parliamentary Labour Party into five tribes: Brexiters such as Frank Field; Re-Leavers like Caroline Flint; those who have so far supported the Labour whip, such as Lisa Nandy; and People’s Vote campaigners, such as Margaret Hodge.

In the boxes are the middle groups, on neither extreme of the Brexit debate. The polling evidence suggests the number in those middle three groups – those in parliament who either Jeremy Corbyn or Theresa May would be focusing on to back a Brexit compromise – represent constituencies increasingly with Leave majorities.

The notion of ‘Brexit Blairism’ underlines the paradox that perhaps the most remarkable similarity between Corbyn and Blair is tolerance for a disjuncture between leadership and membership. More surprising, perhaps, it is a disjuncture that the membership appears willing to tolerate. When asked just before Christmas, 79% of Labour members supported a referendum if May’s deal was rejected in the Commons. Some 61% of Labour members, and 56% of those who voted for Jeremy Corbyn as leader, see Brexit as the most important issue facing the country. 80% would rank it in their top three most-important issues, as would 74% of those who voted for Corbyn. Yet, by a two-to-one margin, these members continue to back Jeremy Corbyn’s approach to Brexit.

This may be because the sequencing and logic of the Labour Party’s conference motion has yet to fully play out, and a referendum has not yet been ruled out by the leadership. It may be because the electoral logic of the Labour Party’s ambiguous policy makes strategic sense to Labour members. It is most likely, however, that loyalty and support for Jeremy Corbyn’s project currently counters any misgivings about his approach to Brexit. As Brexit choices crystallise, this may continue. The salience and importance of Brexit could yet fade before any general election. However, this is a political gamble.

Professor Anand Menon is director of The UK in a Changing Europe and Dr Alan Wager is a research associate.

More from LabourList

Economic stability for an uncertain world: Spring Statement 2026

‘Biggest investment programme in our history’: Welsh Labour commit to NHS revamp if successful in Senedd elections

James Frith and Sharon Hodgson promoted as government ministers