We may be four years away from a general election, but the Labour Party must be alert to the electoral challenges ahead. In this article, I review Labour’s prospects in key constituencies using a crucial criterion: education. In modern politics, education increasingly predicts support for progressive parties such as Labour. I outline routes to (i) a majority and (ii) a minority/coalition Labour government, with specific reference to the number of educated voters in target seats.

Caveats are necessary. A lot could change between now and 2024 – there may be boundary changes, and Scotland might even become independent. Rather than setting out a detailed roadmap, this exercise merely considers potential complexions of Keir Starmer-led governments. People should be mindful of these limitations and should not fixate on individual constituencies.

Scenario one: Starmer majority

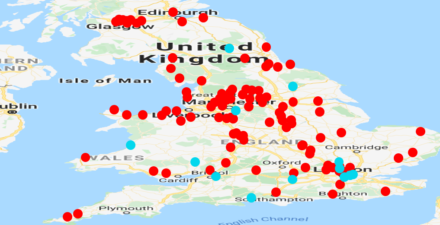

Though many think a Starmer majority unlikely, this possibility should not be dismissed. As Leo McKinstry emphasised in the New Statesman, 67 Conservative seats would fall with a swing of less than 5% – most of them Labour targets. Such a swing might be driven by voter perception of Starmer’s competence, as Ipsos MORI researcher Dylan Spielman argued. The map below depicts Starmer victories in 105 seats, in which the required swing is less than 8.9%. I do not consider seat demographics or the incumbent party. These ‘regular’ Labour gains are in red.

Yet the assumption that swings will be uniform is increasingly problematic, considering factors such as voter dealignment. Rather than make even progress across the country, Starmer is more likely to be successful in particular types of constituencies. Education is a key predictor of support for Starmer. Not only does BES data show that Starmer fares well among those educated to a higher level, but similar politicians are successful among educated citizens across countries.

Given the appeal of Boris Johnson to less educated voters, this cleavage is likely to deepen in coming years. I expand this point in scenario two, but here let’s assume that Starmer makes even more progress in Conservative seats with high proportions of educated voters. In the map, Starmer takes Conservative seats in which the required swing is between 8.9% and 15% and there is an above average presence of voters with degrees.

These ‘educated’ Labour gains are in turquoise. I use data from the 2011 census. Though this is now rather old, better data is not yet available and the distribution is unlikely to have changed markedly. There are other predictors of support for politicians like Starmer, e.g. youth and affluence, but it’s best to keep things simple and education also correlates with other predictors.

There are only 13 of these seats. I had thought there would be more. This underlines the challenge facing Starmer. Adding 105 to 13 and assuming no losses, Starmer nonetheless has 320 seats, which delivers a working majority.

Scenario two: Starmer-led minority government/coalition

Scenario one is far-fetched, in my view. Not only does it require Starmer to win seats with huge Conservative majorities, but he will not necessarily benefit from declining popularity of the Johnson government. Voters unhappy with Johnson could move to the right or abstain. A more likely prospect is a Starmer-led coalition or minority government. This would only require about 50 Conservative losses.

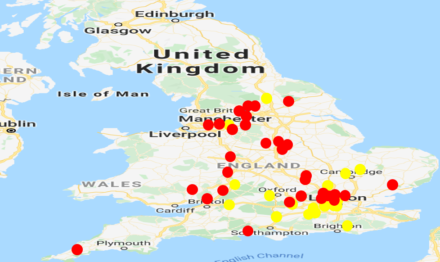

Though some envisage marginal ‘Red Wall’ seats returning to Labour, as modelled above, I’m not so sure. The profile of voters in such seats – older, less educated and poorer – is compatible with Johnsonian Conservatism. If such voters become disillusioned with the current Prime Minister, they are unlikely to vote Labour. The second map therefore shows no uniform swing and depicts Conservative losses only in seats with an above average presence of voters with a degree and a required swings of less than 10%. There are 53 Conservative losses – 32 gains for Labour, 20 for the Lib Dems and one for the SNP.

The gains in the second map are realistic. And though such an outcome may disappoint some Labour activists, it should not. The formation of any Starmer-led government would be a major achievement, given the party’s starting point. If Starmer does make such gains, the Labour voting coalition will nonetheless be different – continuing the move away from traditional supporters.

This may make Labour more socially liberal, but there are major disadvantages. Loss of working-class support lessens redistributive capacity. Because poorer citizens endure material hardship, they prioritise measures that improve their position, middle-class voters being less sensitive to relevant initiatives. This is most concerning because the Labour Party was established to help the poorest.

Below are the seat lists for both scenarios, broken down by ‘regular’ and ‘educated’ gains in the first and by political party in the second.

Scenario one – Starmer majority

Regular gains:

Aberconwy

Airdrie and Shotts

Altrincham and Sale West

Arfon

Ashfield

Barrow and Furness

Birmingham, Northfield

Bishop Auckland

Blackpool South

Blyth Valley

Bolsover

Bolton North East

Bridgend

Broxtowe

Burnley

Bury North

Bury South

Calder Valley

Camborne and Redruth

Chingford and Woodford Green

Chipping Barnet

Cities Of London and Westminster

Clwyd South

Clwyd West

Coatbridge, Chryston and Bellshill

Colchester

Colne Valley

Copeland

Corby

Crawley

Crewe and Nantwich

Darlington

Delyn

Derby North

Dewsbury

Don Valley

East Lothian

East Worthing and Shoreham

Filton and Bradley Stoke

Gedling

Glasgow Central

Glasgow East

Glasgow North

Glasgow North East

Glasgow South West

Harrow East

Hastings and Rye

Hendon

Heywood and Middleton

High Peak

Hyndburn

Ipswich

Keighley

Kensington

Kirkcaldy and Cowdenbeath

Leigh

Lincoln

Loughborough

Midlothian

Milton Keynes North

Milton Keynes South

Morecambe and Lunesdale

Motherwell and Wishaw

Na h-Eileanan An Iar

Newcastle-Under-Lyme

North West Durham

Northampton North

Northampton South

Norwich North

Pendle

Penistone and Stocksbridge

Peterborough

Preseli Pembrokeshire

Pudsey

Reading West

Redcar

Rother Valley

Rushcliffe

Rutherglen and Hamilton West

Scunthorpe

Sedgefield

Shipley

South Swindon

Southampton, Itchen

Southport

Stockton South

Stoke-On-Trent Central

Stoke-On-Trent North

Stroud

Truro and Falmouth

Uxbridge and South Ruislip

Vale Of Clwyd

Vale Of Glamorgan

Wakefield

Warrington South

Watford

West Bromwich East

West Bromwich West

Wolverhampton North East

Wolverhampton South West

Worcester

Workington

Wrexham

Wycombe

Ynys Mon

Educated gains:

Basingstoke

Beckenham

Bournemouth East

Bromley and Chislehurst

Ceredigion

Croydon South

Finchley and Golders Green

Hexham

Macclesfield

Monmouth

North East Somerset

Welwyn Hatfield

York Outer

Scenario two – Starmer-led minority government/coalition

Labour gains:

Altrincham and Sale West

Bournemouth East

Broxtowe

Calder Valley

Chingford and Woodford Green

Chipping Barnet

Colchester

Colne Valley

Derby North

Filton and Bradley Stoke

Harrow East

Hendon

High Peak

Kensington

Loughborough

Macclesfield

Milton Keynes North

Milton Keynes South

Monmouth

Pudsey

Reading West

Rushcliffe

Shipley

Stroud

Truro and Falmouth

Uxbridge and South Ruislip

Warrington South

Watford

Wolverhampton South West

Worcester

Wycombe

York Outer

Lib Dem gains:

Carshalton and Wallington

Cheadle

Cheltenham

Chippenham

Cities Of London and Westminster

Esher and Walton

Finchley and Golders Green

Guildford

Harrogate and Knaresborough

Hitchin and Harpenden

Lewes

South Cambridgeshire

South East Cambridgeshire

South West Surrey

Sutton and Cheam

Wantage

Wimbledon

Winchester

Woking

Wokingham

SNP gain:

West Aberdeenshire and Kincardine

More from LabourList

‘I was wrong on the doorstep in Gorton and Denton. I, and all of us, need to listen properly’

‘Why solidarity with Ukraine still matters’

‘Ukraine is Europe’s frontier – and Labour must stay resolute in its defence’