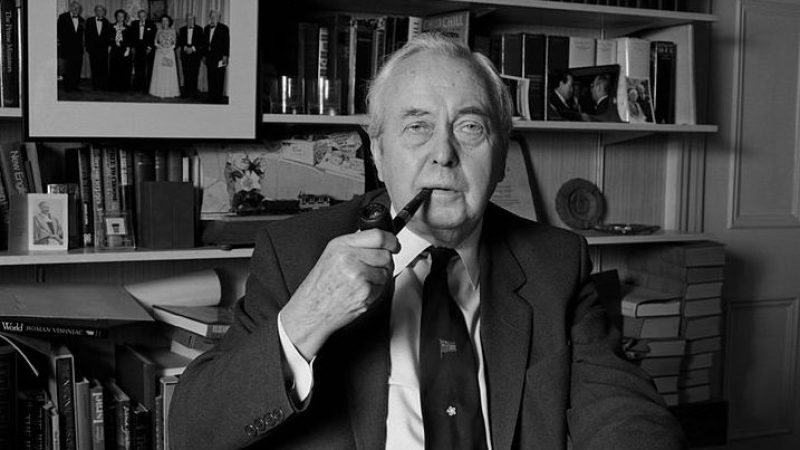

Below is the full text of the Harold Wilson Lecture delivered by Rachel Reeves in March 2021.

Thank you Shirley for that kind introduction. And thanks to Ana and the whole team at the University who have made this lecture happen.

It’s been two years since I first agreed to give this lecture. And 18 months since I was first due to deliver it. A general election and a global pandemic got in the way. But I am delighted to finally be able to do this tonight.

It is great to be back in Bradford, a city in which Labour has deep roots, where the Independent Labour Party was founded, a city with strong links to so many of the stalwarts of past Labour governments, personal heroes of mine like Barbara Castle and Harold Wilson.

Today would have been Harold Wilson’s 105th birthday. A year into a pandemic, which has upended our lives, it is strange to think there is much to gain from reflecting on a Prime Minister who was a product of another age.

Wilson is a Prime Minister who is inextricably tied to a moment of real optimism about the future and about technology. Yet today, in a moment that feels so characterised by insecurity and by uncertainty, I believe there is something important to be salvaged from Wilson’s words about how we relate to change.

Bradford embodies the change that Britain has undergone since the mid-20th century. 70 years ago, a young person living in Bradford might have worked in Lister Mill part of a thriving textiles industry. Today, that young person is more likely to be a nurse or a teacher, or to work in a supermarket or a coffee shop.

Vital work, supporting the foundations of our economy and our society – but different. They might instead aspire to run their own business or to work in the city’s cultural quarter, inspired by a deep history of media, film and television in West Yorkshire.

Today, there are many opportunities for consumption and self-expression unavailable to previous generations. But still young people often face high bills, low wages, and a far greater risk of long-term unemployment or underemployment.

The British capacity for inventiveness and ingenuity and – yes – old-fashioned hard work has not disappeared. It is present as the deep sense of community, which we have seen throughout the pandemic.

My argument is this: technology and the modernisation of our economy and our society have the potential to enrich all our lives – but only if we shape them in the right way. In the national interest, the people’s interest.

Technology can be a driver of shared prosperity or of ever-deepening inequality, depending on how technology, information, power and ownership are distributed and on the rules which govern them.

Labour wants to channel the immense talents and resources we have available; to make sure that technologies old and new are distributed between businesses large and small; and to give all the British people the skills, the agency, the power, and the security to realise their ambitions and live the life they aspire to.

But first: I want to say something about Harold Wilson himself. Second: I want to reflect on how our world has changed – and how our very attitude to change has shifted. And third: I want to talk about Labour’s purpose in that changing world.

So, let me turn the clock back, to the middle decades of the last century. There’s a lot of inspiration to take from Wilson:

- the poster-boy for social mobility;

- the brilliant economist;

- the consummate politician and leader.

Wilson took over a Labour Party that had spent more than a decade struggling to redefine its purpose in relation to a changing society. He would lead that party to four election victories.

Harold Wilson championed a Britain based on merit and talent, not on birth or wealth. Based on policies that make a difference in people’s lives, not those which were most extravagant. And based on a belief that we can harness technology with government, businesses and trade unions working in partnership, to rise to the challenges of the day.

Wilson left behind a country that was more equal, more free and more modern:

- Homosexuality and abortion were decriminalised.

- The death penalty abolished.

- The Equal Pay Act introduced.

- School selection ended across large parts of the country

- The Open University established.

- And more homes built than under any other twentieth century Prime Minister.

And yet, the moment for which Wilson is perhaps most remembered came before all that, when he delivered his sole party conference speech as leader of the opposition before that first election triumph.

It is probably the most famous speech ever made by a leader of the opposition. And it is remembered for Wilson’s reference to the ‘white heat’ of the ‘scientific revolution’. Wilson spoke at a time of real optimism about the benefits that science and technology could bring.

At Labour’s 1960 conference, the party’s general secretary Morgan Phillips had declared:

“The central feature of our post-war capitalist society is the scientific revolution … [which] has made it physically possible, for the first time in human history, to conquer poverty and disease, to move towards universal literacy…”

In such a moment, Wilson’s character seemed to chime with a sense of radical possibility. His Yorkshire roots resonated with the mood of the moment.

As the historian Raphael Samuel reflected: the North in the 1960s stood for ‘radical change’ and ‘the de-gentrification of British public life’, promising “a new vitality, sweeping the dead wood from the boardroom, and replacing hidebound administrators with ambitious young go-getters”.

In 1963, Wilson took aim at a government headed by yet another old Etonian, and at an old boys’ network which constrained Britain’s potential and threatened to lead us in the wrong direction.

An elite which was drawn to the shiniest and the most extravagant new projects, more concerned with their prestige than the productivity of the nation, but which neglected the untapped resources that could be found throughout British society. Perhaps Britain in 2021 would not look so unfamiliar to Harold Wilson.

As the historian James Cronin notes: Wilson’s argument “was in a curious way a perfect reflection of a society and an economy poised on the brink of transformation but not as yet experiencing it”.

People wanted more change. They wanted the extension of opportunity in education and work, to consume and to enjoy new forms of expression. But they also wanted protection – including from the fear of job automation.

Wilson called for a reassessment of where Britain’s resources should be focused, for those areas which prioritised national economic development and the social good.

It was all very well for research to be put into new consumer goods and dazzling futuristic projects but Wilson argued that it was just as important to focus that ingenuity and effort in less fashionable areas, where more people worked and from which more could enjoy the benefits – like food production and agriculture, at home and in the developing world.

Wilson advanced a rallying cry to build a more modern country – with a vibrant economy and a practical politics. His speech stands as the single greatest statement of what Labour has always captured whenever it has succeeded: the harnessing of modernity – of modern values, methods and technology – in the service of prosperity, equality and social justice.

Of putting faith in the ingenuity and talent of the British people, whether in business or politics. And in a better future, one which the Tories could hardly imagine, much less deliver.

Wilson won in 1964 and again – bigger – in 1966 because he aligned himself with the future and with the whole British nation against the vested interests that were holding Britain back.

He believed it was up to all Britain’s institutions to adapt and meet the challenges of the present and the future. As Wilson warned: “he who rejects change is the architect of decay…”

In 1997 too, Labour aligned itself with modernity and change, as the voice of a ‘New Britain’.

- Breathing new life into our public services;

- Introducing the minimum wage;

- Offering new educational opportunities to millions;

- And from the abolition of Section 28 through to the passage of the Equality Act working to make Britain a more equal and tolerant country.

In 1997, I turned 18, and I voted for the first time. The next year, the crumbling buildings at my old school were rebuilt, something we had been calling for years but that had been ignored by the Tories. Labour in government achieved great things.

But over 13 years in power, Labour came to appear too relaxed about the effects of rapid change upon communities which were not the obvious winners of globalisation or of the ‘knowledge economy’.

As well as Labour’s historic victory in the mid 1990s, I remember as a young chess enthusiast going to see Garry Kasparov – probably the greatest chess player of all time – take on the computer programme named Fritz man against machine.

It was extraordinary and exciting – at least it was to me! – to see what programming had achieved and to see Kasparov’s genius talent battle the machine and defeat it.

But it also represents perhaps some of our deepest anxieties about technological change: our fear when we hear that robots will be able to replicate more and more skilled tasks and functions; our sense of real loss when we see the closure of our high-street shops as more of us shop online; the feeling of injustice when the winners of the shift online don’t pay their fair share in tax; and our concern that we won’t be able to keep up with the new technology that’s an increasingly big part of our daily lives.

Change can be disorientating. We feel less secure; less in control of our lives. It can threaten the things we most value: security for our families; the social fabric of our communities; fulfilling, reliable jobs that pay well.

And today: the pandemic; the threat of man-made climate change; the monopolistic power of new digital platforms. These all threaten to rob us of a sense of security and of control over our own lives and communities.

As we look to the future, we worry that our children will not enjoy the opportunities other generations have. We worry that young people will face the difficult choice of pursuing the incredible opportunities our country offers or staying close to those they love, in the place they call home.

We worry that we are becoming a more disconnected society. That in a world of convenience – with everything bought with one click – our public spaces will be left impoverished. We worry about the constant and increasing demands on our attention and our time.

Yet it seems this dogmatic government is unable to address Britain’s insecurity even though we have all seen its consequences over the past year. On the eve of the pandemic, almost one million people were employed on zero-hour contracts and 11-and-a-half million adults had savings of less than £100.

Now: the fantastic work of the GMB to defend and extend the rights of workers in the gig economy is to be lauded. And the Supreme Court’s ruling that Uber drivers are workers and entitled to rights as workers is welcome. And it will make a big difference to the lives of ordinary working people in Bradford, Leeds and across the country.

Our insecurity in the face of change is relates to older, deeper questions than technology questions which would be familiar to those trade unionists in the late nineteenth century who sought to extend to all women workers the trade union protections enjoyed by textile workers in Bradford and beyond about regulation of the labour market, rights at work, and how to organise workers in precarious employment.

While we might associate these new platform giants with big tech their business models frequently rely on much older technologies: vans, cars and bicycles. And as the RSA argues, it is low rates of unionisation and collective bargaining not the inexorable march of automation which is the biggest brake on good work in the UK.

The pandemic has affected us all – but it has not affected us all equally. It has thrived upon inequalities of wealth, race, place and disability and in many cases, it has made those inequalities deeper. Millions of self-employed – hard-working, enterprising people – have been left excluded from government support throughout the pandemic.

And even now: our rate of statutory sick pay remains among the lowest in Europe leaving many workers facing the choice between putting food on the table or protecting their community by staying at home and self-isolating.

The pandemic has led to other changes, too. Millions of people have begun to work from home, and many are likely to stay there. This offers exciting new opportunities for people to move out of big cities, or for families to spend more time together.

Amidst this most global of crises, for many of us, our lives have become more local. We place more value than ever on our green spaces – our parks and countryside.

And on our relationships: children who bring a smile to our faces at the end of the day, even if that day has been spent home schooling; the grandmother you’ve taught to use FaceTime; or the friends you have missed so much.

In its cruellest moments, the pandemic has robbed us of the chance to be with loved ones at the end of life. But even in the most challenging of times, we have seen the strength and resilience of our communities.

Research by Together, a coalition of organisations chaired by Nick Baines, the excellent Bishop of Leeds, has found: that overwhelmingly people across the country believe that the experience of the pandemic has made their community more united and that the public’s response to the crisis has shown the unity of our society more than its divisions.

12.4 million adults have volunteered during the pandemic 4.6 million of them for the very first time. As we emerge from this crisis, we need to ask ourselves how can we preserve, enhance and draw upon what is best about Britain in a world that sometimes feels beyond our control?

That potential is clear. It is extraordinary to think how different our experience of this pandemic would have been just a few decades ago when it would have been unthinkable for so many people to work, study or connect with friends and distant family from inside our own homes or to use data to track the spread of the virus.

We have seen during the pandemic how technologies can transform how we interact with public services whether it is Zoom parents’ evenings, or online GP appointments pointing the way towards a more responsive, efficient state.

And the vaccine has shown how science with government, businesses and universities working hand-in-hand can solve the biggest and most daunting challenges of our age.

But we must ask ourselves: if the vaccine shows the incredible capacity of the public and private sectors to collaborate in response to a problem as big as a pandemic in the most trying of conditions then why have successive Tory governments over more than a decade been so slow to address the other big challenges of our age whether that is eradicating child poverty, or ensuring that everybody can grow old with dignity?

Or indeed: reaching net zero and tackling the climate emergency a task around which Britain’s resources of scientific expertise, ingenuity and determination can be mobilised.

There are opportunities to seize as well as challenges to be met. Look at the technologies which offer the potential to reduce our carbon emissions from electric cars, to Carbon Capture and Storage, to hydrogen power.

A challenge of this scale calls upon government to bring businesses, unions, universities and the British public together to deliver huge change. And in so many of these sectors, we will lead from Yorkshire and across the North of England.

With leadership from government, it is possible to modernise and green our existing industries; to develop new, dynamic industries for the future; to provide good work here in the UK – that is well paid, rewarding and secure; to make our homes more energy efficient; to provide the infrastructure for green transport and strong connectivity; and yes, to build more pleasant, green places in which we can all live.

As Ed Miliband, Labour’s Shadow Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, has argued… drawing on the work of the economist Mariana Mazzucato this will form part of a mission-based approach towards reviving our manufacturing industries and meeting the great challenges of our age.

So: while we can see the potential for positive change all around us, in many places, what we have seen is too little change. And too much potential has been left untapped.

Take our low levels of public and private investment in British businesses and the stark reality that, in the context of a pan-European productivity slowdown, we still lag behind our neighbours. Investment and our most productive firms remain overwhelmingly concentrated within a few areas of our country.

In an economy often defined by wealth extraction more than wealth creation shareholders are encouraged to prioritise short-term returns rather than the long-term investment that can generate shared prosperity.

So: where private wealth was once an engine of innovation and growth, today it too often sits stagnant and inactive. The UK spends less today on Research and Development today than it did in Wilson’s time.

And of that spending: 53% is directed at London, the South East and East of England. The comparative total for the entire north – from Newcastle to Bradford, Wigan to Grimsby, and everywhere in between – is just 16%.

While parts of London and a few urban centres enjoy the benefits of huge investment, much of Britain remains characterised by a low productivity, low growth and low wage economy. The budget offered no answers on the future of science and research in the UK

- with no detail on the replacement of Horizon funding;

- nothing for early career researchers;

- and no plan to support science jobs in all regions of the UK.

And the very same week we heard:

- That the government has decided to abolish its Industrial Strategy Council;

- And the OBR revealed that the government’s much-heralded National Infrastructure Bank is likely to have precisely no effect on growth and is a puny 147 times smaller than its German equivalent.

Britain is a great country. Our scientists, universities, and the creative talents and commitment of the British people can do extraordinary things which we have seen this past year.

We can discover vaccines, drive up growth, drive down emissions and reduce inequalities between places and people.

But it is not enough to focus on the small number of firms that are the most innovative, the most productive and even the best paying if the majority of businesses are frozen out.

Part of the response is to broaden our focus – as Wilson did paying more attention to those low-wage, low-productivity, high-employment sectors which form the foundations of our economy and of all our communities.

Those without which we could not live decent, healthy lives as individuals or communities. These everyday parts of our economy include social care, food production, supermarkets, utilities, retail and more.

And as the historian David Edgerton tells us, we must emphasise ‘imitation’ at least as much as ‘innovation’. In other words: how are we to learn from best practice from the most successful firms in Britain and around the world? And how are we to ensure uptake of new approaches and technologies among the majority of firms?

As the Bank of England’s Chief Economist Andy Haldane has argued by shifting our attention from productivity and innovation among a small number of frontier firms concentrated in London and the south-east towards the many more businesses in Britain which do not have access to the newest technology and insights it may be possible to boost the quality of work and wages for the many while also tackling our productivity puzzle.

While the government talks a good game about its plans for levelling up it will take a much more radical departure from our ways of seeing the economy to deliver widely shared prosperity, good work and good places to live for everyone.

Digital exclusion has driven the growing gap between the prospects of the best and least well-off young people during the pandemic while whole regions are held back by poor digital infrastructure.

If we want to close the gap between north and south between city, town and country and between rich and poor then we need good digital infrastructure for small businesses and start-ups in every part of Britain and indeed in every home.

We need every child to have access to the opportunities for education and participation which access to a laptop and a decent internet connection can provide. And if we are to ensure no talent is wasted, that will mean addressing the chronic lack of women studying or working in science and tech.

As I have argued in this lecture, technology is not an external, uncontrollable force. We have the capacity to shape change. Too little change, too little investment, too little regulation leave us more exposed and more insecure in the face of a turbulent world.

If we are to extend opportunity in a changing economy, it is up to us to ensure everybody can develop skills and knowledge over the course of their lifetime.

Harold Wilson understood that equal educational opportunity was the route not just to equal chances, but also to the national interest to ensure that no talent was wasted and the country could harness all its resources.

It is up to an activist, competent government working with business, unions and more to ensure we seize opportunities within a changing world and ensure all our people have power, freedom and opportunity.

Labour’s history is a history of nation-building, of creating a thriving national economy on strong, secure foundations. That task remains as relevant today as it was in 1964. As Labour has always done in its greatest moments, Wilson spoke for the whole nation against vested interests.

We have been through a lot together as a nation over the last year. So many people have sacrificed so much. As we look to the future, we see competing visions for how reward, sacrifice and opportunity are shared in a post-pandemic world.

We have seen the government’s answer: a real-terms pay cut for NHS staff – and crony contracts for their friends and donors.

Labour’s alternative is a more secure United Kingdom in which reward and opportunity are shared fairly – between people and places in which power will be shared fairly across England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland in a new constitutional settlement.

A country in which everyone plays their part in the national effort. As Keir Starmer said, this work will require “a new partnership… between an active government… enterprising business… and the British people”.

In this changing world, our ambition remains the same as that which Harold Wilson defined in 1963: to unleash ‘all the latent and underdeveloped energies and skills of our people’ to provide the foundation for a stronger, wealthier and fairer country. It will be a national undertaking.

More from LabourList

Nudification apps facilitate digital sexual assault – and they should be banned

Diane Abbott suspended from Labour after defending racism comments

Labour campaign groups join forces to call for reinstatement of MPs