Who governs Britain? You don’t have to be a Marxist or conspiracy theorist to wonder if the opaque workings of global finance sometimes count for more in politics than the will of politicians and the public.

Labour MPs are reportedly now being warned that rebelling against cuts or tax hikes will “incur the displeasure of the market” after the same was said of a leadership challenge.

Meanwhile Keir Starmer responded to Andy Burnham’s suggestion we get “beyond…being in hock to the bond markets” by invoking Liz Truss – who even CNN described as “defeated by the bond market”.

The Starmer-Burnham divide encapsulates a broader left debate. Some are resigned to bond market power; others rail against it. The million-dollar question is – is there an alternative?

LabourList asked experts if Britain is as in hock as widely perceived, and whether apparent alternatives are feasible or fantasy – from looser fiscal rules to Jeremy Corbyn’s ‘people’s quantitative easing’.

But in a complex area even for economists, it’s best to begin at the beginning. What are the bond markets?

How do government bond markets work?

When governments predict tax won’t cover spending, they borrow. They ask potential lenders for funding now, by selling an IOU repayable in several years’ time.

That IOU is a bond. British ones are called ‘gilts’; American ones, ‘Treasuries’.

The incentive for bond buyers, like mortgage lenders, is the interest governments pay in the meantime, often in twice-yearly payments called ‘coupons’.

Bonds are also traded between investors too.

If a new £100 bond pays £5 annual interest, investors gets a 5% ‘yield’ on their investment.

But if they buy one second hand for £80 – say if worries about Trussonomics or better opportunities abroad bring lower prices – the £5 interest looks even better, as the return or ‘yield’ on their £80 rises to 6.25%. Plus, they earn £20 if the bond is held until ‘maturity’ – i.e. repayment.

So the less investors want government debt, the lower the price, and the higher the yield.

Headlines about rising yields – a common way the media report on debt – are therefore bad news for government.

Saturday’s FT WEEKEND: Investors lose faith in Reeves Budget#TomorrowsPapersToday pic.twitter.com/q3466Z08FL

— Jack Surfleet (@jacksurfleet) November 14, 2025

They signal investors will demand higher interest when new bonds are next issued, diverting cash from public services.

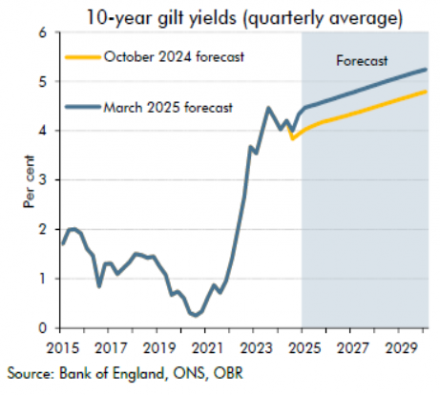

Alarmingly, last week saw the biggest rise in yields since July as investors questioned how Reeves could fix public finances without income tax hikes.

Is government in hock to bond ‘vigilantes’?

Bondholders are often portrayed as sinister forces. The New Statesman’s current cover features masked ‘bond vigilantes’.

Yet steady, safe income makes UK pension funds and insurers the biggest buyers. “Know it or not, you’re probably investing in bonds,” one expert tells LabourList.

The NS acknowledges traders are also just people “you queue behind” in cafes.

Being ‘in hock’ is also in the eye of the beholden.

Michael McMahon is dismissive. “If you want to be free, don’t have plans that require you to convince people to lend you money,” says the Oxford University economics professor.

Few people would lend to strangers without reward for the risk, and some idea how they’ll repay. The riskier the loan, the higher the interest.

Spending rows hide long-term spending trend

Last week’s yield spike underlines Reeves’ problem. Her socialism still means spending colossal sums of other people’s money, however Scrooge-like constant spending rows seem.

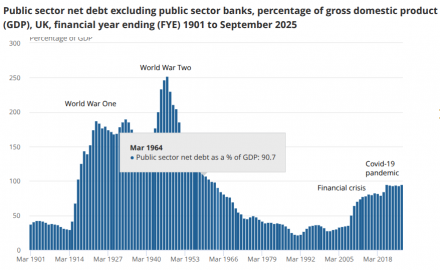

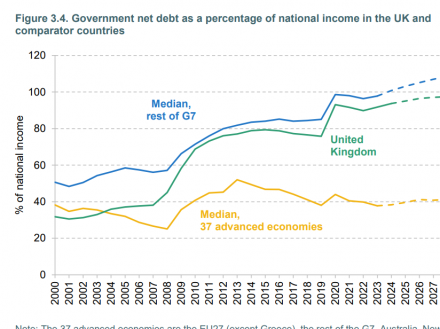

She rightly blames her inheritance. Government debt is now almost as high as the value of all goods and services produced in Britain (GDP).

The Tories left debt levels 47% higher than Labour left in 2010 relative to GDP, and more than double 1979 levels.

Debt skyrocketed following the 2008 crash and then Covid, both for bailouts and everyday spending as tax revenues plummeted.

“It’s unprecedented outside world wars,” says the Resolution Foundation’s James Smith, adding that weak growth hampered efforts to reduce debt.

Meanwhile ageing populations are raising spending, notes former BBC economics correspondent Steve Schifferes.

There’s a “general sense it’s at the top of what can be tolerated”, one economist says.

No more cheap money tree

Yet debt can be manageable when interest rates are low. The problem is they no longer are.

The government pays £64 billion more interest annually than just three years ago – a rise as big as the schools budget.

Inflation, driven by Covid and Ukraine supply disruption, is partly to blame, with bondholders expecting higher interest to stop bonds’ real-terms value falling.

But crucially, new bonds must be competitive with rates buyers could secure elsewhere. Governments globally are issuing far more bonds, and another arm of UK government arguably isn’t helping, either. Not only has the Bank of England hiked wider interest rates to eight times above levels in the 2010s to curb inflation, it’s also now selling off bonds cheaply that it bought during Covid.

The Truss and Trump premiums – and Labour’s own goals

Higher debt, inflation and interest rates globally contribute to yet another factor pushing up all governments’ borrowing costs – the risk premium. Government defaults are rare, but fears over repayment are edging higher.

Some argue confidence in Britain is still affected by Liz Truss, but Labour U-turns on welfare and income tax haven’t helped, either. Markets want “reassurance government can make decisions and follow through,” one economist says.

Nor has the far smaller margin Reeves leaves herself to meet fiscal rules than most predecessors, and the far smaller toolkit, having ruled out austerity and hiking key taxes. Chris Hayes of think tank Common Wealth notes minuscule forecast downgrades have prompted continual speculation tax rises will follow to plug the gap. That in turn hit damaging investor and business confidence.

Tax Hikes to ‘People’s Quantative Easing’: Can we break free?

Classical economics offers an intuitive answer: cut spending. But as Labour MP and economist Jeevun Sandher recently wrote, cuts can harm growth, as the 2010s “doom loop” showed.

One left alternative is to raise taxes. “If we want better roads, schools and hospitals, the way it’s paid for is taxation,” says McMahon.

Subscribe here to our daily newsletter roundup of Labour news, analysis and comment– and follow us on Bluesky, WhatsApp, X and Facebook.

Hayes suggests taxing capital gains, dividends, land and expensive homes more. The Resolution Foundation also recently proposed £30 billion of tax hikes, from VAT and fuel to income tax.

But Reeves’ has fallen into line with every other Chancellor since 1945 in shying away from basic rate increases – which illustrates the political problem.

READ MORE: ‘To win back trust, Labour needs a clear dividing line on tax’

Another left proposal is printing money to cover spending. Jeremy Corbyn once proposed ‘people’s quantitative easing’, suggesting the Bank of England buy bonds to directly fund housing and infrastructure.

The Bank did use its ‘magic money tree’ to stave off the financial and Covid crises, buying government debt en masse.

Hayes suggests a Bank mandate tweak to at least stop its current bond sales effectively undercutting the government’s.

READ MORE FROM THE ARCHIVE: What is Corbyn’s QE proposal?

But McMahon argues Covid was exceptional “life support”, whereas any whiff of political interference would mean investors demand a higher premium.

Many experts agree central bank independence from politicians generally keeps inflation and interest rates down.

Another radical proposal is controls on capital leaving Britain, indirectly pushing investors towards gilt-buying. But it would hammer international investment, and Britain’s finance industry.

The less radical options – and the likely ones

Changing Britain’s fiscal rules or budget watchdog’s mandate is a less radical option. Most economists interviewed agreed investors can swallow rule changes in principle. “We’ve had nine different rules in 15 years,” one notes, adding that the Tories missed targets too.

Reeves has loosened the rules already, but some argue the government’s credibility is too damaged for immediate rule changes.

“The rhetoric’s more important than actual figures. Markets are based on trust in people running government, and its stability,” says Schifferes. “No objective amount of debt’s impossible to finance, but people are a little nervous.”

Reeves’ apparent answer is twofold. First, raising her ‘headroom’ or margin for error meeting fiscal rules, seemingly through varied tax hikes.

READ MORE: Budget 2025: Full list of Labour MPs backing wealth tax motion

Second, focusing on growth. “If we’d grown at the path we were on before the financial crisis, we’d have tax receipts £200 billion higher,” says Smith.

Growth also makes debt smaller relative to GDP – a key way debt is measured – without actually cutting it.

Hayes says more infrastructure investment is key; for Schifferes, it’s upskilling managers.

Labour Business committee member Martin Bailey says Reeves actually need not “change course”, with current planning reforms and investments likely to bear fruit.

Share your thoughts. Contribute on this story or tell your own by writing to our Editor. The best letters every week will be published on the site. Find out how to get your letter published.

For some, growth could rebuild trust in Reeves to gradually borrow more, if plans will clearly boost it further.

But kickstarting growth has proved a long-running, Europe-wide headache.

Whatever the approach, Labour politicians are more united in trying to get beyond being in hock to bondholders than recent rows suggest.

-

- SHARE: If you have anything to share that we should be looking into or publishing about this story – or any other topic involving Labour– contact us (strictly anonymously if you wish) at [email protected].

- SUBSCRIBE: Sign up to LabourList’s morning email here for the best briefing on everything Labour, every weekday morning.

- DONATE: If you value our work, please chip in a few pounds a week and become one of our supporters, helping sustain and expand our coverage.

- PARTNER: If you or your organisation might be interested in partnering with us on sponsored events or projects, email [email protected].

- ADVERTISE: If your organisation would like to advertise or run sponsored pieces on LabourList‘s daily newsletter or website, contact our exclusive ad partners Total Politics at [email protected].

More from LabourList

‘Labour won’t stop the far right by changing leaders — only by proving what the left can deliver’

‘Cutting Welsh university funding would be economic vandalism, not reform’

Sadiq Khan signals he will stand for a fourth term as London Mayor