“Labour policy is directed to the creation of a humane and civilised society.” So announced Labour’s Appeal to the Nation, the party’s 1923 manifesto.

This was the one on which it fought the general election that saw Ramsay MacDonald become Prime Minister and form in January 1924 the first Labour government, inaugurating what the party recently described as its Century of Achievement.

A document of little more than 1,000 words, it was very different to Labour’s 23,000- word long manifesto which this week was launched across all media platforms. The 1923 manifesto was a wonderfully vague document with hand-waving references to Labour’s commitment to the scientific organisation of industry, the abolition of slum housing and equality between men and women.

It even concluded with an appeal to voters ‘to oppose the squalid materialism that dominates the world today’. If this suited the windy rhetoric of Labour’s leader the manifesto still promised the party would nationalise the coal, rail and electricity industries as well as impose a wealth tax on fortunes in excess of £5,000 (the equivalent of £400,000 today).

MacDonald signed off on these commitments, which pleased many in his party, expecting to see the return of Stanley Baldwin’s Conservatives to government.

MacDonald saw the manifesto like the Greens do today

Just like the Green Party leadership today he saw the election as a propaganda opportunity, to build up the party vote and win a few more seats. Just like everybody else MacDonald was shocked to find himself, thanks to the vagaries of three-party competition under first past the post, forming a minority administration.

The alacrity with which MacDonald set aside the most eye-catching policies in the manifesto was criticised by the Labour left some of whom urged him to present it in full to the Commons and dare Liberal and Conservative MPs to vote it down.

That, they inevitable would have done, after which the left wanted MacDonald to call another election thinking it would mobilise more support for their idea of socialism.

READ MORE: ‘No surprises, but fear not: Labour manifesto is the start, not the end’

Instead, hoping to demonstrate they could be trusted to hold the reins of government, MacDonald and his Cabinet followed a more cautious course, trying to win support in the Commons for a variety of more modest reforms the most notable of which was the 1924 Housing Act. This provided central government funds to subsidise the building of over half a million council homes until it was repealed in 1933.

The legislation had not even been thought of when the manifesto had been written. As a result of MacDonald’s fast-and-loose attitude to the manifesto Labour increased its vote at the December 1924 election by nearly 25 per cent although it still lost office.

Wilson had no intention of delivering manifesto wealth tax pledge

Since then, Labour leaders coming from opposition into government have had a variable and complicated relationship with their party’s manifesto. At one extreme was Clement Attlee whose government more than lived up to the promises of Let Us Face the Future in 1945 – although much of that programme had already been put into practice during the Second World War.

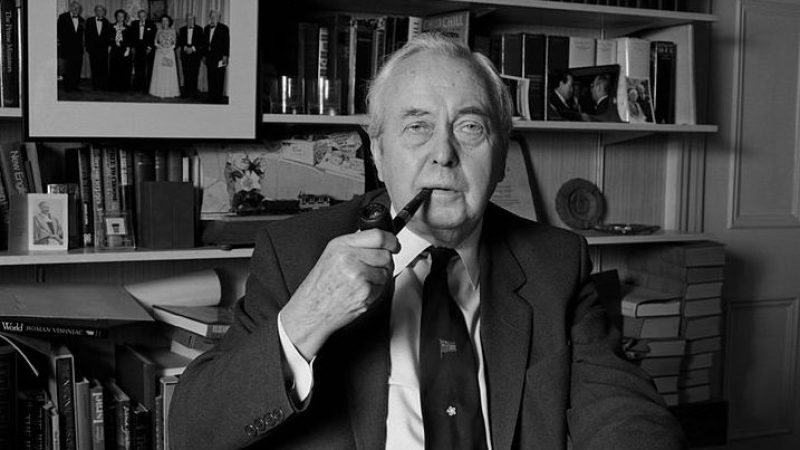

At the other end of the spectrum was Harold Wilson. Labour’s February 1974 manifesto promised to introduce a wealth tax as part of ‘a fundamental and irreversible shift in the balance of power and wealth in favour of working people and their families’. This Wilson had absolutely no intention of delivering.

READ MORE: ‘Labour manifesto shows a new centrism – with the state key to driving growth’

Like MacDonald, Wilson was taken aback when he found himself unexpectedly at the head of a minority government even though Edward Heath’s Conservatives had won more votes. Even after winning a modest Commons majority in October Wilson set his face against the platform on which he had ostensibly won power.

For this ‘betrayal’ Wilson and his successor Jim Callaghan was not forgiven by the Labour left, which took its revenge after Labour lost in 1979, blaming defeat on the failure of the Parliamentary leadership to live up to the manifesto’s socialist ambition. Labour’s manifesto this time round has been written with the intention of providing Keir Starmer with a relatively ‘serious’ and ‘fully-costed’ programme for government.

Could Labour still opt for a wealth tax?

Evoking Labour’s 1997 manifesto – and not just in how heavily it features pictures of the Labour leader – it falls short of what many in the party would like to see. But it makes concrete if modest commitments, the success of which can subsequently be measured by a sceptical electorate.

There is certainly no talk of a wealth tax this time as part of Starmer’s attempt to avoid any hostages to fortune this side of the election that might still be exploited by the Conservatives and its many allies in the media.

READ MORE: ‘The manifesto’s not perfect, but at the launch you could feel change is coming’

In the eyes of some of the left that’s because Starmer has got in his ‘betrayal’ early by setting aside many of the ten pledges he made to win the leadership in 2020 and abandoning the commitment to spend £28 billion annually on green projects.

It is also a reaction to the much-criticised ‘over-loaded’ 2019 Corbynite manifesto which looked incredible to many of those voters the party wants to recapture in 2024. The one benefit of this under-loaded manifesto is what it promises it will likely do – Labour will be in deep trouble if not – and by under-promising it could over-deliver.

Who knows maybe there will – at long last – be wealth tax of sorts in Rachel Reeves’ first Budget?

Find out more through our wider 2024 Labour party manifesto coverage so far…

OVERVIEW:

Manifesto launch: Highlights, reaction and analysis as it happened

Full manifesto costs breakdown – and how tax and borrowing fund it

The key manifesto policy priorities in brief

Manifesto NHS and health policies – at a glance

Manifesto housing policy – at a glance

Manifesto Palestine policy – at a glance

Manifesto immigration policies – at a glance

ANALYSIS AND REACTION:

‘The manifesto’s not perfect, but at the launch you could feel change is coming’

IPPR: ‘Labour’s manifesto is more ambitious than the Ming vase strategy suggests’

Socialist Health Association warns Labour under-funding risks NHS ‘decline’

‘The manifesto shows a new centrism, with the state key driving growth’

Fabians: ‘This a substantial core offer, not the limit of Labour ambition’

‘No surprises, but fear not: Labour manifesto is the start, not the end’

‘What GB energy will do and why we desperately need it’

‘Labour’s health policies show a little-noticed radicalism’

GMB calls manifesto ‘vision of hope’ but Unite says ‘not enough’

IFS: Manifesto doesn’t raise enough cash to fund ‘genuine change’

Watch as Starmer heckled by protestor with ‘youth deserve better’ banner

POLICY NEWS:

Labour vows to protect green belt despite housebuilding drive

Manifesto commits to Brexit and being ‘confident’ outside EU

Labour to legislate on New Deal within 100 days – key policies breakdown

Labour to give 16-year-olds right to vote

Starmer says ‘manifesto for wealth creation’ will kickstart growth

Read more of our 2024 general election coverage here.

If you have anything to share that we should be looking into or publishing about this or any other topic involving Labour or about the election, on record or strictly anonymously, contact us at [email protected].

Sign up to LabourList’s morning email for a briefing everything Labour, every weekday morning.

If you can help sustain our work too through a monthly donation, become one of our supporters here.

And if you or your organisation might be interested in partnering with us on sponsored events or content, email [email protected].

More from LabourList

Paul Nowak column: ‘Labour must focus on the basics’

‘Labour’s two-child cap victory rings hollow while asylum-seeking children remain in poverty’

SPONSORED: ‘Unlocking pension power to boost the UK’s fortunes’