A century ago, European politics stood at a crossroads. The old order had broken down, but nothing stable had replaced it. Financial crisis had shaken faith in markets. The global balance of power was shifting. Patterns of work and life were being reorganised at speed, pulling people from regions into cities, from agriculture into industry, from tradition into uncertainty.

What followed was not inevitable, but political.

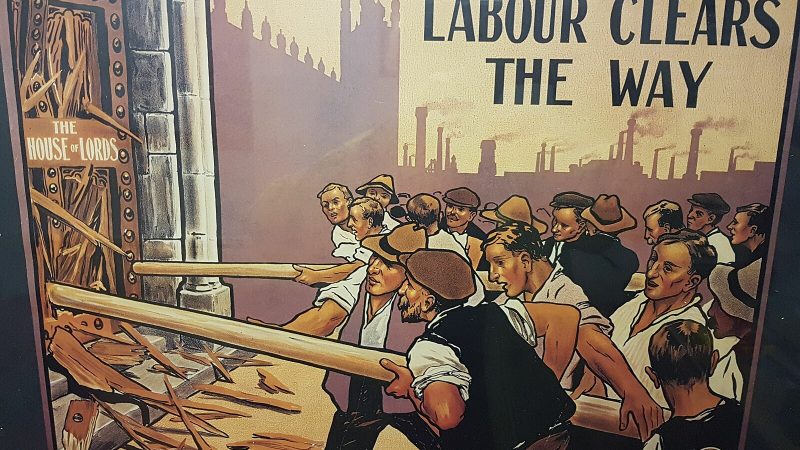

Across Europe, three broad responses emerged. Fascism offered certainty through hierarchy, nation, and order. Communism promised equality through collective ownership and rupture with capitalism. Social democracy took a different path: taming markets, expanding democratic control, and building institutions that made individual dignity compatible with mass society.

politics must offer direction

The lesson of that period is not just that fascism can win. It is that when societies are disoriented, politics must offer direction. And when democratic movements fail to do so, authoritarian ones step in.

It will not have escaped readers that we are living through a remarkably similar moment.

READ MORE: ‘If we don’t define our ends, populists will define them for us’

The past two decades have delivered repeated shocks: the 2008 financial crisis, the pandemic, a cost-of-living crisis, climate breakdown, and now geopolitical instability as US global dominance weakens and a more fragmented world takes shape. Work has become more insecure and more mobile, with regional economies hollowed out and opportunity concentrated in a handful of cities. Housing has become a speculative asset rather than a social good. Public institutions have been stretched thin or quietly dismantled.

Once again, people experience power everywhere (in markets, algorithms, prices, rents) but struggle to locate it politically. Decisions shape their lives without appearing as decisions at all.

This is the terrain on which today’s far right is advancing.

Like its predecessors a century ago, contemporary far-right movements do not simply react to economic anxiety. They offer a moral story that makes sense of it. They re-centre “the people” as a collective with shared values, shared enemies, and shared destiny – defined not civically, but culturally, through race, gender, tradition and hierarchy. Belonging is promised, but only on condition of conformity.

And crucially, this politics does not challenge the economic order that produced insecurity in the first place. It adapts to it.

Fascist movements often used anti-capitalist language. But historically, once in power, they preserved private ownership, crushed organised labour, and reorganised capitalism around hierarchy and national loyalty rather than equality. Capitalism was preserved, but embedded within a rigid moral order.

We are seeing the same dynamic today, in the context of neoliberal capitalism.

Far-right politics offers certainty without redistribution. It explains inequality not as a consequence of ownership or power, but as a result of cultural failure, moral weakness, or external threat. It privileges the interests of a narrow and already powerful sector of society, while redirecting anger away from those who benefit most from the system.

welfare chauvinism

This is why far-right movements can talk about “the people” while defending tax cuts for the wealthy, weak labour protections, and speculative housing markets. Hierarchy is not a bug; it is the point.

It is also why what has been termed welfare chauvinism fits so comfortably within this politics. This refers to the far right’s fleeting moments of advocating for seemingly left-wing economic policies. Limited forms of redistribution are not rejected outright, but rationed morally as rewards for the “deserving”, the loyal, the properly belonging. Support is offered not as a matter of equal citizenship, but as a badge of membership.

Subscribe here to our daily newsletter roundup of Labour news, analysis and comment– and follow us on TikTok, Bluesky, WhatsApp, X and Facebook.

This explains some of the politics of winter fuel payments. Reform’s moment of sounding more redistributive than Labour was not a leftward shift, but a case of welfare chauvinism. Welfare is tolerated when it can be directed at a morally approved in-group – implicitly white, older, national, and culturally conforming – and rejected when it risks benefiting those cast as outsiders.

In this framework, redistribution is not about equality but about boundary-drawing. Support for pensioners can be defended as care for “our own”, while housing, disability or migrant support is framed as unfair transfer to the undeserving. Welfare becomes a cultural instrument, not an economic one. For the far-right, the state may act, but only to preserve hierarchy. Anything that threatens the hierarchical distribution of wealth or power is ruled out in advance.

The agreed way out of the crisis we faced in the 20th century, was a social democracy. The tragedy is that we have never decisively rejected social democracy. We have simply drifted away from its economic and institutional substance. Our social democracy was dismantled privatisation by privatisation, labour reform by labour reform, until ownership slipped from democratic hands to private ones.

Over several decades, Britain moved from a political economy that treated housing, work, utilities and public services as shared infrastructure, to one that treats them as markets to be managed. Democratic control was replaced with regulation. Ownership was depoliticised. Collective provision was reframed as inefficiency.

This shift did not come with a grand ideological declaration. It arrived through reforms, compromises, and adaptations – each presented as technical, pragmatic, unavoidable. Politics narrowed. Governance expanded. And the social-democratic promise that democracy could shape the economy, rather than merely cope with it, slowly faded from view.

What remained was a politics fluent in process but increasingly silent about purpose.

What is a left politics actually for?

This is the context in which Labour finds itself today. Leadership matters, but leadership alone cannot answer a crisis of direction.

If Keir Starmer is now more responsive to the Labour base, our pressing question is not whether we change leaders or messaging, but whether we can articulate what a left politics is actually for in these conditions. Appeals to “growth” are not enough. Growth without a vision of who benefits, who owns, and how life improves risks reproducing the very disorientation the far-right exploits.

The task is not to recreate the 20th century, but to recover its lesson: that in moments of upheaval, democracy only survives when it is made tangible. Not as an ideal, but as something people can see and touch in their daily lives – a secure home they cannot be priced out of, a job that does not vanish overnight, a bus that turns up, a GP appointment that exists, a workplace where their voice matters.

That is what once gave democratic politics its credibility. Council housing did not just house people; it rooted them. Public ownership did not just lower bills; it made shared fate plausible. Trade unions did not just bargain over wages; they taught people that power could be exercised collectively rather than endured individually.

Share your thoughts. Contribute on this story or tell your own by writing to our Editor. The best letters every week will be published on the site. Find out how to get your letter published.

When those institutions were dismantled or hollowed out, something deeper was lost: the sense that society was organised for ordinary people rather than merely managed around them. In that vacuum, hierarchy rushes in, offering belonging without equality and certainty without security.

What Labour needs now is not simply better leadership, but the confidence to rebuild a social-democratic culture equal to the moment. Labour must speak proudly about ownership, security and shared institutions. We must offer people a stake in a future that they can recognise as their own.

-

- SHARE: If you have anything to share that we should be looking into or publishing about this story – or any other topic involving Labour– contact us (strictly anonymously if you wish) at [email protected].

- SUBSCRIBE: Sign up to LabourList’s morning email here for the best briefing on everything Labour, every weekday morning.

- DONATE: If you value our work, please chip in a few pounds a week and become one of our supporters, helping sustain and expand our coverage.

- PARTNER: If you or your organisation might be interested in partnering with us on sponsored events or projects, email [email protected].

- ADVERTISE: If your organisation would like to advertise or run sponsored pieces on LabourList‘s daily newsletter or website, contact our exclusive ad partners Total Politics at [email protected].

More from LabourList

Delivering in Government: your weekly round up of good news Labour stories

‘Outflanked on both sides: why Labour is losing touch with the economy’

‘Labour’s lesson from Denmark: immigration alone won’t save you’